Food industry

The food industry is a significant element of the bioeconomy. This is where agricultural products are processed into food and animal feed. Resource-efficient technologies help to produce healthy, high-quality and safe products.

Examples of bioeconomy:

Vitamins, flavourings and amino acids,

sweeteners, functional foods,

sausage, meat and cheese substitutes

With around 6,000 companies and 645,000 employees, the food industry is one of the largest sectors in Germany. According to the Federation of German Food and Drink Industries (BVE), the total turnover in 2023 was almost 230 billion euros. The sector is very much characterised by small and medium-sized enterprises, with 90% of the companies employing fewer than 250 people.

Many of the operations are family businesses with a long tradition or manufacturers of regional German specialities with a strong international client base. The most important sub-sectors of the food industry are the meat and meat products industry, the dairy industry, the confectionery and bakery industry, beverage production and the processing of fruit and vegetables. The wide variety of products reflects this diversity. For the bioeconomy, the food sector is an important sub-sector. Around 80% of agricultural produce in Germany is processed into high-quality food products. Strategies for recycling waste products from the food and feed industries are becoming increasingly important.

Reaching into nature’s toolbox to enhance our food is not a new trick. After all, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or bakers’ yeast, has been used for beer brewing and wine making for thousands of years. The conversion of substances with the help of microorganisms is called microbial fermentation. Lactic acid bacteria turn milk into yoghurt and other dairy products. They help to preserve food and feed, such as for example in the cases of sauerkraut or silage. For milk to become cheese, the rennet enzyme has to curdle the protein within the milk. Rennet used to be obtained from calves’ stomachs. Today, tailor-made microorganisms enable biotechnological processes to take place in large steel tanks to produce these useful molecules upon which cheesemaking depends at industrial scale.

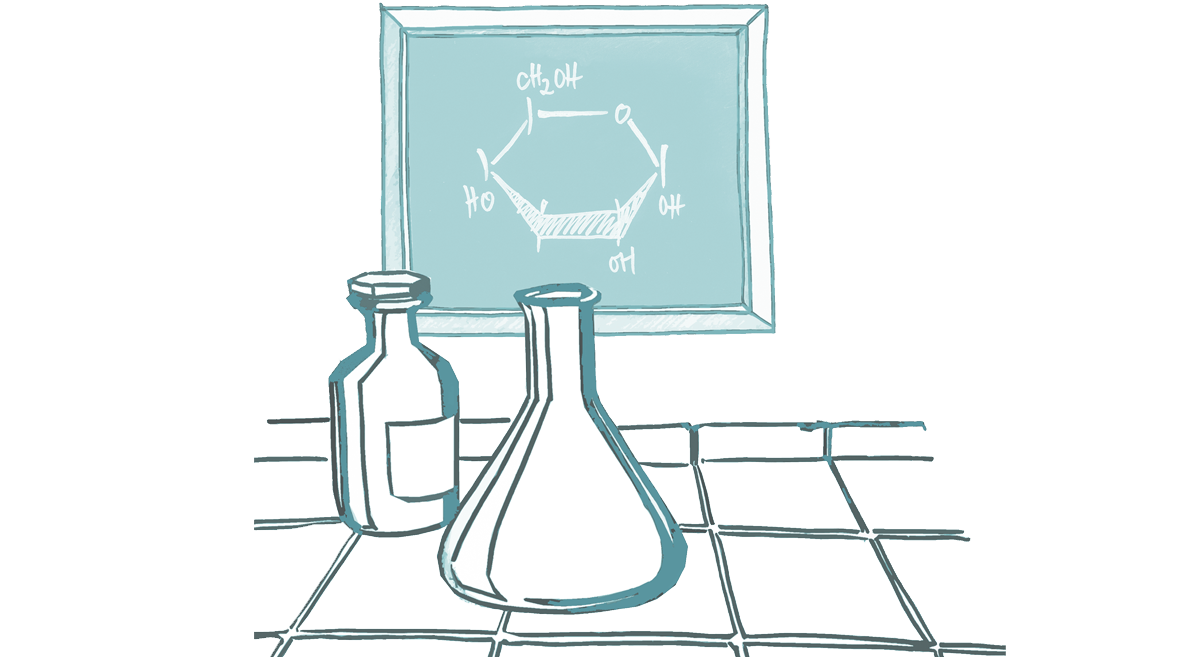

Enzymes in action

The food industry uses enzymes as natural bio-catalysts for many purposes. Since the 1960s, microbial processes inside digestors have become the standard for the production of enzymes. Around 50 different enzymes are currently being used in the food industry. About 20 companies in Germany produce enzymes, from large chemical corporations like BASF to small and medium-sized enterprises. Some of these companies receive funding from the BMBF and the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action.

Enzymes are resource-efficient multi-talents that work in a very targeted manner and are mostly active under mild conditions (low temperatures, neutral pH, aqueous environment). The baking industry employs special enzymes to produce an appetising and stable bread crust. Other enzymes are added to the mix in order to add volume and colour. Pre-made dough products for baking on the premises, which have become popular in bakeries, would not even be possible without such enzymes.

Some raw materials can be enriched and used more efficiently with the help of enzymes. Pectinases, for example, help to break down the cell wall of fruit for more efficient extraction and clear turbidity in the fruit juice. Lactase splits lactose (milk sugar) into smaller molecules, which makes it another important enzyme for the food industry. Lactase is also available as tablets or in capsules to help people with lactose intolerance digest dairy products.

Natural flavourings are often produced on the basis of enzymatic and microbial production processes. Strawberry flavouring, for example, originates in mushrooms, while peach flavouring is extracted from yeasts. Citric acid was the first food additive to have been produced biotechnologically on a large scale. It is no longer extracted from citrus fruit, but through a process which uses the mould Aspergillus niger as a cell factory and which today provides the entire global production volume (2 billion tonnes). The food industry uses citric acid, or E 330, as an additive for soft drinks, sweets, to acidify bread and in meat processing. Another important group of food additives, amino acids, is also produced biotechnologically. These basic building blocks of proteins can provide a sweet taste, while others smell like oranges or like lemons. The salts of glutamic acid (glutamate) are used as flavour enhancers. Three million tonnes per year are produced worldwide with the help of the bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum.

Essential amino acids such as lysine, threonine and methionine cannot be produced by organisms themselves. They are very important feed additives, with more than two million tonnes of lysine produced for the animal feed industry worldwide every year. One of the major producers of amino acids for animal feed is the specialty chemicals group Evonik.

Sweeteners are a key component of many foods. In response to lifestyle diseases such obesity or diabetes, there is a trend towards lower-calory food ingredients. In particular, the demand for ingredients that taste sweet but do not contain household sugar is rising. Stevia glycosides from the tropical plant Stevia rebaudia are often used as a low-calory alternative as they have almost 200 times the sweetening power of normal sugar. Researchers are working on producing stevia glycosides using a biotechnological process. It is actually possible to produce highly pure individual components – such as steviosides and rebaudiosides. Unfortunately, many stevia glycosides have a metallic, slightly bitter aftertaste. To counteract this taste, c-Lecta, a biotech company from Leipzig, makes an enzyme which can be used for the production of rebaudioside M, which has no bitter aftertaste.

Brain Biotech AG, a biotechnology company from Zwingenberg which is part of the DOLCE research alliance, has identified more than 60 plant-based molecules that could be used as sugar substitutes or sweetness enhancers. Brain Biotech and the French company Roquette will bring the production of brazzein, a sweet-tasting protein extracted from a West African fruit, to industrial scale.

Brazzein was investigated as part of the strategic alliance NatLifE 2020, which was coordinated by Brain Biotech. The consortium was co-funded by the BMBF and had more than 20 partners. The objective was the joint research of natural substances that can be used as flavour changers or mask a bitter taste – such as that of the stevia sweeteners mentioned above.

Functional foods are another new trend in the food industry. Functional foods can have a positive effect on a person’s health, in particular as prevention. Prebiotic substances, which include special dietary fibres, are considered functional ingredients. They can favourably affect the community of microorganisms in the gut, or microbiome. Probiotic dairy products contain live strains of bacteria that are thought to improve the balance of the microbiome when ingested. Certain secondary plant substances such as polyphenols or glucosinolates are also considered to be beneficial to health. In a BMBF-funded project, secondary plant compounds are harvested from plant residues from sweet pepper cultivation which are suitable as food supplements. Jennewein Biotechnologie (part of Chr. Hansen since 2020) receives funding from the BMBF in order to develop a biotechnical process for the production of human milk sugars to be used as an ingredient for baby food.

The growing health and environmental awareness among the European population has led to rising demand for plant-based, sustainable alternatives to meat, and food producers are responding. Vegetarian and vegan meat and dairy alternatives have become mainstream. There is no other part of the food industry that is growing as strongly as that of substitutes for food of animal origin.

While plant-based products made from soy and wheat have long been used as alternative protein sources, the focus is now shifting to the domestic cultivation of protein-rich crops. Lupins are the most noticeable protein-rich crop grown in Germany on account of their colourful flowers. Lupin seeds contain around 35% of protein. For a long time, lupin seeds were shunned by the food industry because of their high content in bitter components but now researchers have been able to identify a variety that contains fewer bitter alkaloids and is very disease-resistant – the blue lupin (Lupinus angustifolius). What’s more, this legume is easy to grow and thrives particularly well in northern Germany. Nodule bacteria on the roots of sweet lupins bind nitrogen, which means that they also fertilise the soil.

The start-up Prolupin GmbH, a spin-off of the Fraunhofer Institute for Process Engineering and Packaging IVV in Freising, has developed a process for the extraction of lupin protein – which has a very neutral taste – from the seeds. The company was awarded the German Federal President’s Award for Technology and Innovation in 2014. Based in Mecklenburg-Antepomerania, Prolupin extracts lupin protein as well as fibres, oil and shells. The latter are also suitable as food additives. The company also produces and markets its own products such as ice cream, desserts and milk substitutes.

The BMEL supports the development of plant-based protein alternatives with research funding from the Protein Crop Strategy. One example project investigates the potential of lupin varieties which are rich in bitter components as a protein source. Their high alkaloid content makes these plants more disease-resistant and easier to grow than sweet lupins. The goal of the project is to remove the bitter components using modern process engineering.

Other BMEL research initiatives aim to optimise native grain legumes such as peas for use in innovative foods. One hurdle is that the starch quality in peas varies significantly. To find out more about their starch properties, two hundred pea varieties are being cultivated as part of the research project.

Meat and cheese from the laboratory

Industrial meat production uses up enormous resources, which damages the climate and the environment. There are also ethical concerns and concerns about animal welfare. Innovative cell culture technology offers new options for more sustainable food production. More and more researchers and companies are considering the production of meat and fish from cell culture (cultured meat). Meat is usually grown from muscle stem cells or other cells that are capable of reproduction in a bioreactor. Innovative players in Germany include the Rostock-based start-up Innocent Meat and the Berlin-based start-up Bluu Seafood. Berlin-based start-up Formo wants to conquer the market with vegan mozzarella and other substitute dairy products (photo). They have developed a biotechnological process using yeasts to produce casein and whey protein – the molecules responsible for the taste and texture of dairy products – in the laboratory. The start-up uses these molecules to produce various cheese substitutes based on vegetable fats.

Even though products based on insect proteins still occupy a small niche of the German food industry, a few start-ups have started offering insect-based products. One such company is Bugfoundation, which has now become part of Kupfer Innovative Food. Bugfoundation has developed insect burgers whose patty contains large amounts of ground Buffalo worms. The Cologne-based start-up SWARM Protein started off selling fitness bars based on insect protein from crickets, but has since shifted its focus to dog food.

The BMBF funds several projects exploring the potential of insect-based products for food and animal feed. This work is carried out by the Innovation Area “NewFoodSystems” as well as several consortia within the funding initiative Agricultural Systems of the Future. The food4future collaboration project tests the breeding of crickets for urban food production, while the CUBES Circle network pursues the vision of intelligent networking of different agricultural production systems for plants, insects and fish in closed energy and material cycles. The network feeds the larvae of the soldier fly, which are ideal recyclers of food waste or other by-products of the food industry, to silver carp and tilapia.

There are a number of bioeconomy research projects working on recycling food industry waste within a bio-based circular economy. Upcycling offers companies in the food industry a great way of developing a range of new products with added value from these sidestreams.

One such project is the BMBF-funded CocoaFruit consortium, which is coordinated by Fraunhofer IVV in Freising and based on a cooperation with Indonesian partners and German companies. The goal is to use every part of the cocoa fruit and to develop innovative foods and ingredients from it. The cocoa beans – the basis of chocolate – only make up 10% of the cocoa fruit. The remaining 90%, the shells and pulp, are hardly used. One idea is to use the cocoa shells as a substrate for the cultivation of mushrooms to be used for the production of sausage substitute products. The pulp is used as a basis of fruit preparations and beverages. Upcycling concepts also include alcoholic spirits made from whey, snacks made from excess fruit and beer made from discarded bread.