Foodstuffs packaging has a variety of functions: The product has to be protected against humidity and oxidation, but also against mechanical stresses. Therefore containers or bags – whether of plastic or paper – are often coated with a special material consisting of several thin layers of different glued plastics to form a durable protection against external influences. To ensure that neither water vapour nor oxygen impair the quality of meat or cheese, up to seven layers are needed. The problem: The adhesives used to keep these layers together, such as polyurethane, are generally mineral oil based and do not make a good barrier against oxygen. Researchers from the Fraunhofer Institute for Process Engineering and Packaging (Fraunhofer-Institut für Verfahrenstechnik und Verpackung, IVV) in Freising have now discovered a plant-based alternative – that actually performs better.

The discovery that proteins stick

As part of the 'Barrier adhesive for foodstuffs packaging based on vegetable micelle proteins' joint project, Andreas Stäbler and his team selected residual matter from agriculture as a potential source of raw materials. For it has been known for some time that proteins form effective barriers against oxygen. But the Fraunhofer researchers happened upon their adhesive properties more or less by chance. "Following precipitation of extracted proteins, the technicians who had to clean the apparatus kept complaining how sticky the stuff is," reports project manager Andreas Stäbler. This irritating secondary effect was to prove highly useful, however. The idea of developing a plant-based adhesive with a barrier function was born.

Testing agricultural raw materials as protein sources

The three-year research programme has been supported by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung) with a total of 300,000 euros since 2014 as part of the 'New products for bio-economics' idea competition. In the pilot phase from August 2014 to April 2015 the work was concentrated on testing an existing protein production method on a range of raw materials. After this, the product that was developed could be used as a basis for an initial adhesive formula.

Lupin proteins as forerunners

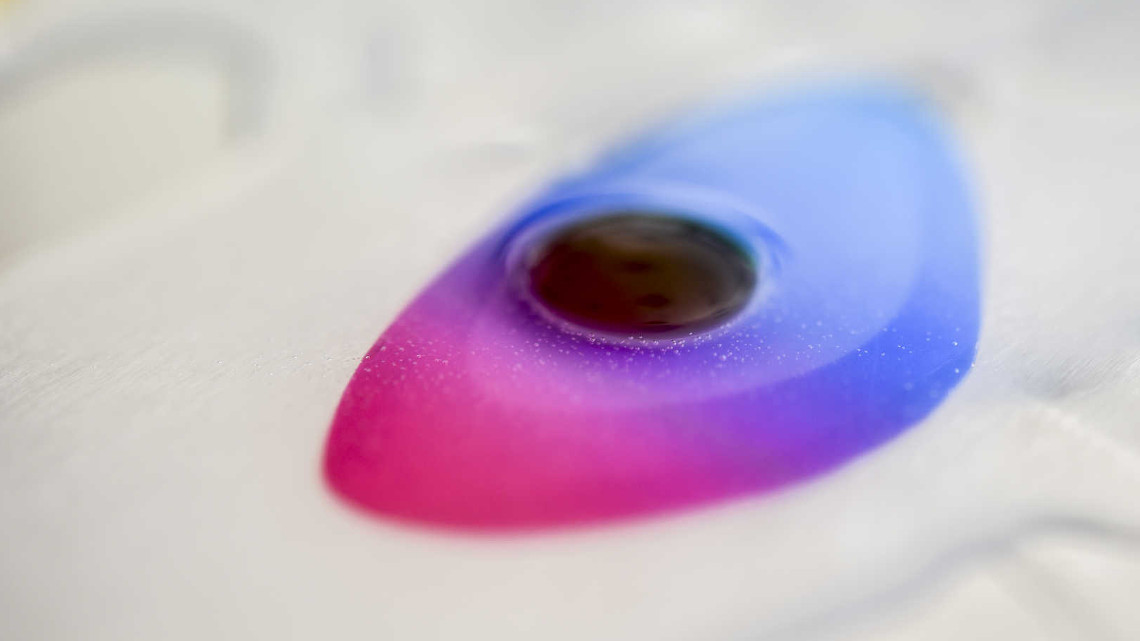

The starting point for the research work was a method for producing micelle proteins from lupins that had been optimized in previous projects. This involves sudden dilution of proteins that have been extracted with the aid of a saline solution. "The resulting ionic shock causes a change in the protein structure. It accumulates to spherical aggregates – so-called micelles. This structural refolding is what causes the stickiness," explains Stäbler.

In investigating agricultural residues, the researchers concentrated their attention especially on oil production waste, such as press cakes from sunflower and rapeseed oil production. At the same time, the new precipitation method was tested on bitter lupins. As a result, however, the researchers found that the protein production method could not be applied as effectively on other raw materials without modification. Thus the sunflower and rapeseed press cakes produced considerably lower yields than the lupins at first. In the meantime, the researchers believe they have found the reason for this. "We think the differing results from the extraction process can be put down to the amino acid structures specific to the raw materials, which lead to individual spatial arrangement patterns," explains project participant and bio-engineer Daniela von der Haar.

Increased micelle yield for rapeseed and sunflowers

"We are now able to achieve high quantities of micelle proteins from rapeseed and sunflower press cakes as well," says project manager Andreas Stäbler. So it proved to be possible to adapt the production process to cater for various raw materials as early as the current feasibility study.

Improving the adhesive properties of the lupin

Regarding the adhesive formula, there is still some work to be done. For instance, the micelle proteins from lupins showed good oxygen barrier values, but their adhesive effect was not as good as that of mineral oil based polyurethane systems. The researchers are now concentrating their efforts on improving the adhesive effect. In this respect, softeners such as glycerine or sorbitol show some promise. "By now we have been able to achieve a very good bond between paper and plastic. So far, though, when it comes to sticking plastic to plastic the residual water does not dry off sufficiently – we need to optimize this more," reports Stäbler.

The researchers hope that by the end of the two-year feasibility study in the coming year they will have solved this problem as well. "We have a functioning water-based system. But in the end we want to develop an adhesive system that can be used in other packaging systems as well," says von der Haar. To this end, the Fraunhofer team is working together with the Technical University of Munich and the Detmold adhesives manufacturer Jowat SE.

Reducing adhesive layers and costs

As well as the participating adhesives manufacturer from Detmold, other companies in that sector as well as firms from the packaging and film treatment industry are showing interest in the plant-based barrier adhesive. But the bio-adhesive would be suitable for more than just the protection of foodstuffs. It would also provide a natural means of protecting electronic components from oxidation. "We want to combine the properties of barrier adhesive, bonding agent and oxygen barrier in a single material. This would allow us to reduce the number of layers needed from currently seven to three, namely paper, barrier adhesive and plastic layers. That would amount to cost savings of up to 40 percent," explains Andreas Stäbler.

Author: Beatrix Boldt