Glass microalgae as a bioindicator for coastal marshes

Researchers at the University of Rostock were able to demonstrate the positive environmental changes following the rewetting of a coastal moor on the island of Rügen using the diatom.

Moors are not only unique habitats for animals and plants. They bind large amounts of climate-damaging CO2 and therefore make an important contribution to climate and environmental protection. However, the proportion of intact moors in Germany is rather low at just under 5 %. Efforts are therefore being made in many places to revitalise moors that were once drained. Using the coastal moor ‘Polder Drammendorf’ on the island of Rügen in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania as an example, researchers from the University of Rostock show how the environment has changed as a result of rewetting in this area.

As part of the study, a team led by Prof Dr Ulf Karsten investigated the microalgae communities before and after rewetting. The focus was on the so-called microphytobenthos. These are microalgae that live on the bottom of bodies of water. They perform up to 30 % of photosynthesis in coastal ecosystems and therefore make a significant contribution to the ecological stability of sediments.

Diatoms as bioindicators

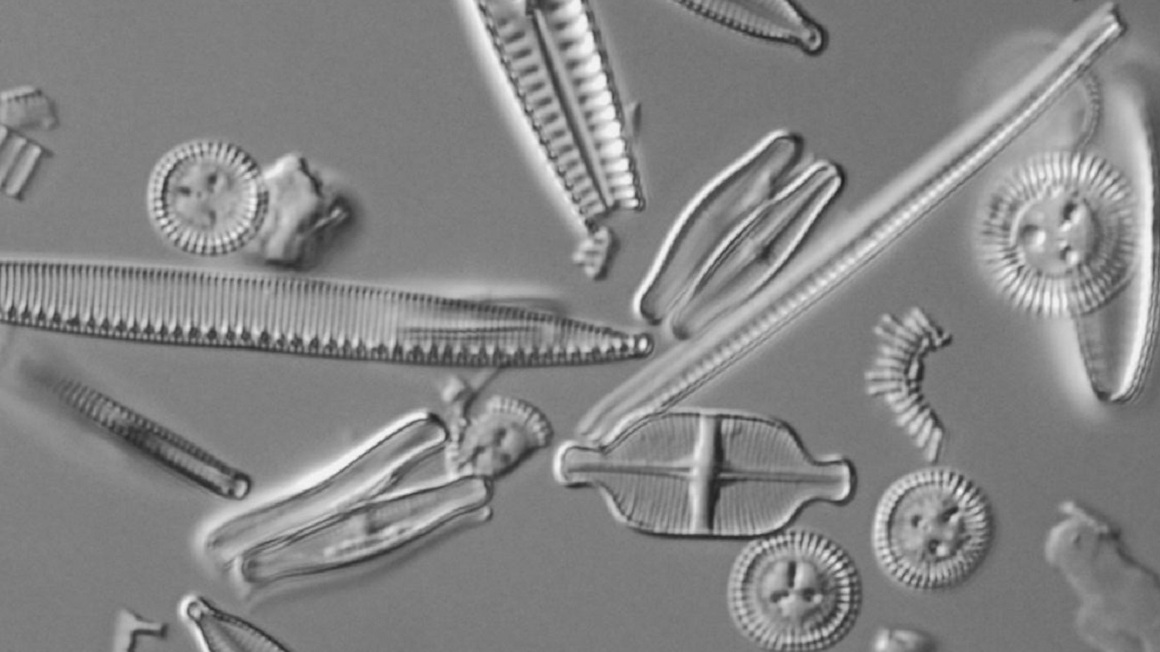

This microbial community also includes diatoms, which ‘play a central role’ in the evaluation of the ecosystem, as the study by the Rostock researchers shows.The reason: diatoms react sensitively to environmental changes. As the team writes in the journal Science of the Total Environment, the microalgae with their glassy, mineralised cell wall thus serve ‘as bioindicators that document changes in the habitat and make them interpretable’.

‘Thanks to their adaptability and their role as bioindicators, diatoms make an important contribution to identifying the most important changing environmental factors, to coastal protection and ultimately to understanding these sensitive and unique ecosystems,’ emphasises Karsten.

Microalgae react to the rewetting of moors

Information about the new environmental conditions in the rewetted moor was provided by the so-called glass shells of the diatoms, which were collected and analysed after the rewetting of the coastal moor Polder Drammendorf. The study shows how flexibly and adaptably these microorganisms ‘react to flooding and how well they can map environmental changes in dynamic coastal systems’.

‘We were able to show the effects of flooding in the coastal marsh and the neighbouring Kubitzer Bodden and document a high diversity of species, including some previously unknown species,’ says Konrad Schulz, lead author of the study. ‘The results also show that the flooding has led to permanent changes in the composition of the microphytobenthos in the bog and even to temporary changes in the Bodden.’

Help for future renaturalisation projects

The study by the Rostock researchers not only provides important insights into the ecological changes in coastal bogs after rewetting. With their help, future renaturalisation projects could also be planned in a more targeted manner, they say.

bb