New method identifies taste molecules

Certain protein fragments give cheese, beer, soy and the likes their characteristic taste. Munich biochemists have developed a new method to identify these fragments.

Many foods such as cheese, yoghurt, beer, yeast dough or soy sauce have a special characteristic taste and are therefore very popular. So-called non-volatile substances in particular are the basic building blocks for these unique taste profiles. These building blocks in turn consist of fragments of long protein molecules that are formed during the microbial or enzymatic conversion (fermentation) of milk or cereal proteins. However, there are more than a thousand different variants of these fragments, and it is still unclear which of them are responsible for the respective taste profile.

New process identifies taste molecules

A research team led by Thomas Hofmann, head of the Department of Food Chemistry and Molecular Sensor Technology at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and director of the Leibniz Institute for Food Systems Biology, has now developed a new, time-saving and more cost-effective analytical method to identify the taste-giving protein fragments.

According to their report in the "Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry", the new method of the Munich bioechemists combines established methods from proteome research and sensory research. This enables them to quickly and efficiently identify the protein fragments they are looking for. "We coined the term 'sensoproteomics' for this type of procedure," says Andreas Dunkel from the Leibniz Institute of Food Systems Biology, who was also involved in the study.

New method identifies 17 flavour molecules out of 1,600 possibilities

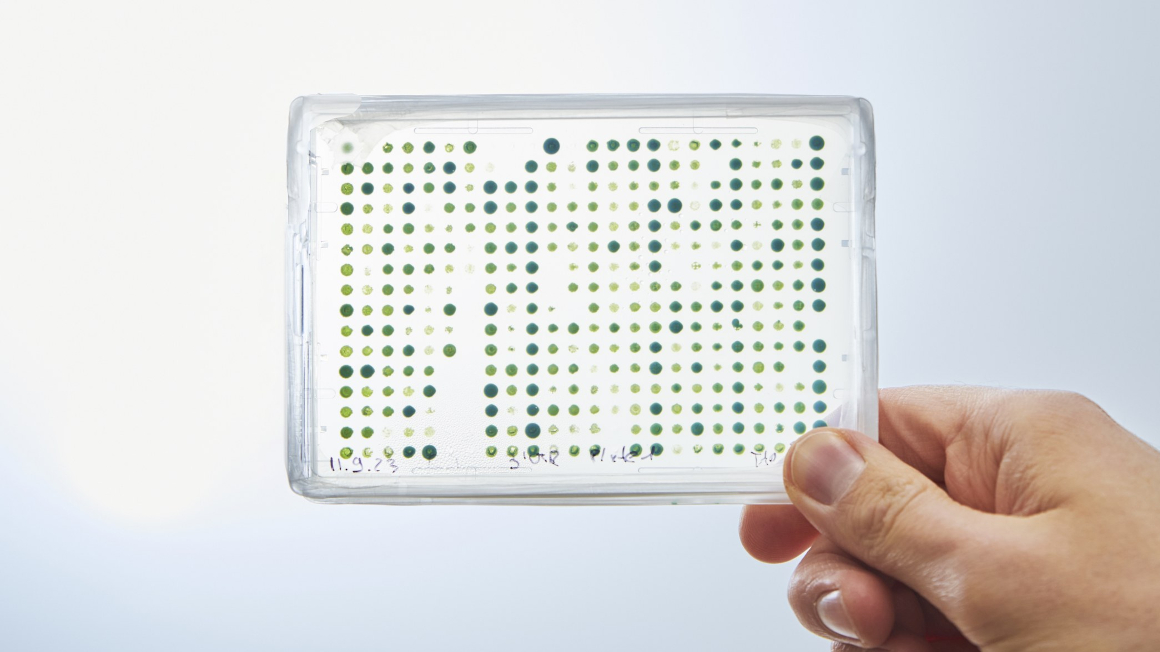

In order to test their new method, the team investigated two different types of cream cheese that differ in their bitterness. The aim was to find out which protein fragments caused this difference in taste. According to a literature analysis, it could have been one of 1,600 fragments. Using initial chemical exclusion procedures and the new combinatory method, the research team succeeded in reducing the number of possible protein fragments that cause the difference in bitternes down to 17. "The 'Sensoproteomics' approach we have developed will in the future contribute to the rapid and efficient identification of flavour-giving protein fragments from a wide range of foods using the high-throughput method - a significant help in optimising the taste of products," says Hofmann.

The project was funded by the German Federation of Industrial Research Associations "Otto von Guericke" e.V. within the framework of the programme for the promotion of joint industrial research of the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi).

jmr