Seagrass meadows store more CO2 than thought

The plants secrete large amounts of sugar into their root zone, but only a few species of bacteria feed on it.

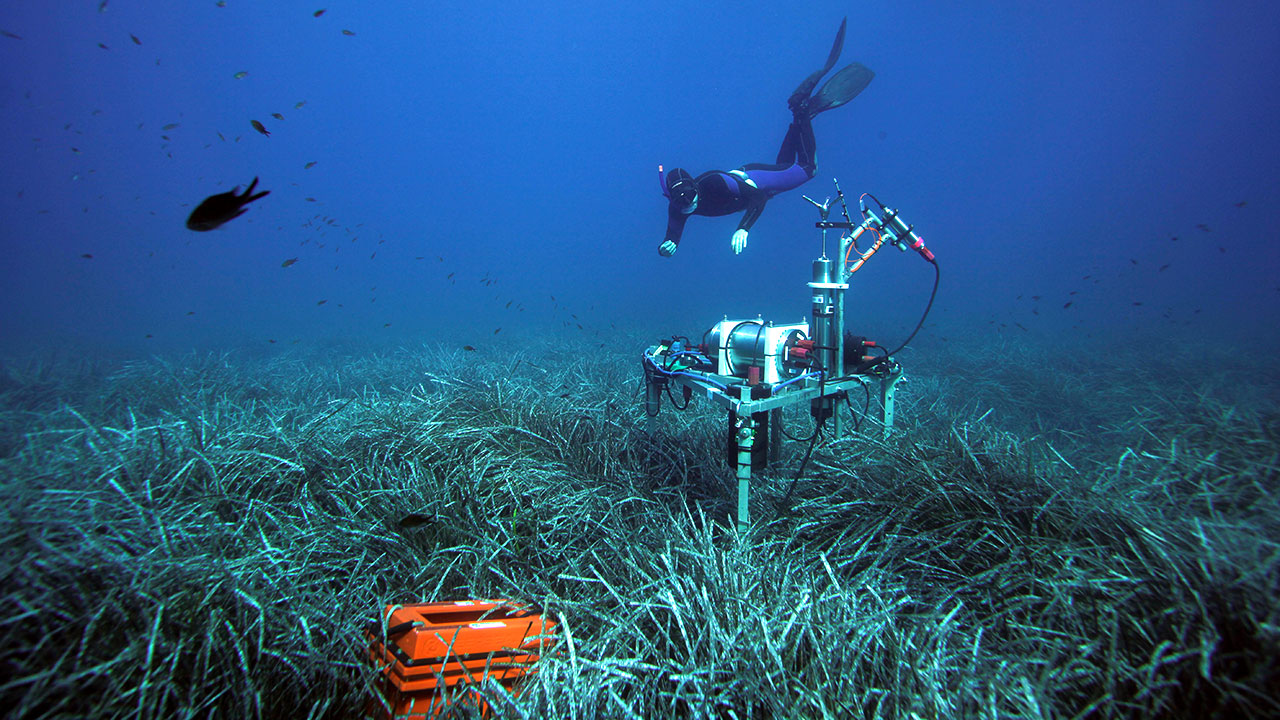

Seagrass removes carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere more sustainably than previously thought. This is the conclusion of a study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, which examined seagrass meadows off the island of Elba. The marine plant is known to be very efficient at sequestering CO2 that is released from the atmosphere into seawater. Seagrass eliminates almost twice as much greenhouse gas as an average forest of the same size. Now it has been shown: A large part of this carbon remains longer than suspected on the seabed - or more precisely: in the seabed.

Up to 1.3 million tons of sugar

A research team from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen has discovered that plants secrete large amounts of sugar into their root space, known as the rhizosphere. "We estimate that between 0.6 and 1.3 million tons of sugar, mainly in the form of sucrose, are stored in the seagrass rhizosphere worldwide," reports Max Planck researcher Manuel Liebeke.

Normally, this sugar would not remain there for long: It is a welcome source of food for microorganisms. But only a few specialized microbes seem to be able to survive in larger numbers in the root zone of the seagrass, because the plants also secrete large quantities of phenols there. These substances can inhibit the metabolism of many microorganisms. "We conducted experiments in which we exposed the microorganisms in the seagrass rhizosphere to phenols isolated from the seagrass - and indeed, much less sucrose was consumed there than when we had not added phenols," describes Maggie Sogin, first author of the study.

Excess feeds possible symbionts

The research team has a theory as to why seagrass invests so much energy from photosynthesis to produce sugar, which it then secretes again: "Under average light conditions, the plants use most of this sugar for their own metabolism and growth," explains Nicole Dubilier from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology. "But under very strong light, for example at midday or in summer, they produce more sugar than they can consume or store." The secretion is thus equivalent to an overflow valve, she says.

The specialized bacteria that feed on this sugar despite the phenols probably secrete molecules that benefit the seagrass, such as nitrogen. "We know such beneficial relationships between plants and microorganisms in the rhizosphere well from land plants. But we are just beginning to understand the intimate and complicated interactions of seagrasses with microorganisms in the marine rhizosphere," Sogin explains.

Seagrass avoids 1.5 million tons of carbon dioxide annually

The research team has calculated that around 1.5 million metric tons of CO2 would be released into the atmosphere if the sugar in the root zone of the seaweed were completely degraded by microorganisms. This would be equivalent to the annual emissions of 330,000 cars. However, the global stocks of seagrass are declining rapidly. Experts estimate that one third of the global population may already have disappeared over the past decades. Preserving the corresponding coastal ecosystems would therefore be important not only from a nature conservation perspective, but also for climate protection.

bl