Artificial metabolic pathway sets new standards

For the first time, an international research team has been able to optimize synthetic carbon fixation to such an extent that it works more efficiently than natural metabolic pathways.

In nature, CO2 is mainly fixed via the Calvin cycle, which is part of photosynthesis. Marburg microbiologist and Leibniz Prize winner Tobias Erb has been working for some time on making natural fixation pathways more efficient with the help of synthetic biology.

Now a team led by Erb at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Marburg and Nico Claassens at Wageningen University in the Netherlands has achieved a key breakthrough: For the first time, the researchers have been able to show that synthetic carbon fixation can work more efficiently in living systems than its natural counterparts. As now described in the journal Nature Microbiology, they succeeded in integrating an artificial metabolic pathway into a genetically modified bacterium. As a result, it was able to produce significantly more biomass from formic acid and CO2 than natural bacterial strains.

Synthetic biology improves CO2 fixation

“It is fascinating that we can use synthetic biology to design new solutions within a few years that work more efficiently than what has evolved in nature over billions of years,” says Erb. For him, the work represents a significant step forward for the young field of synthetic biology.

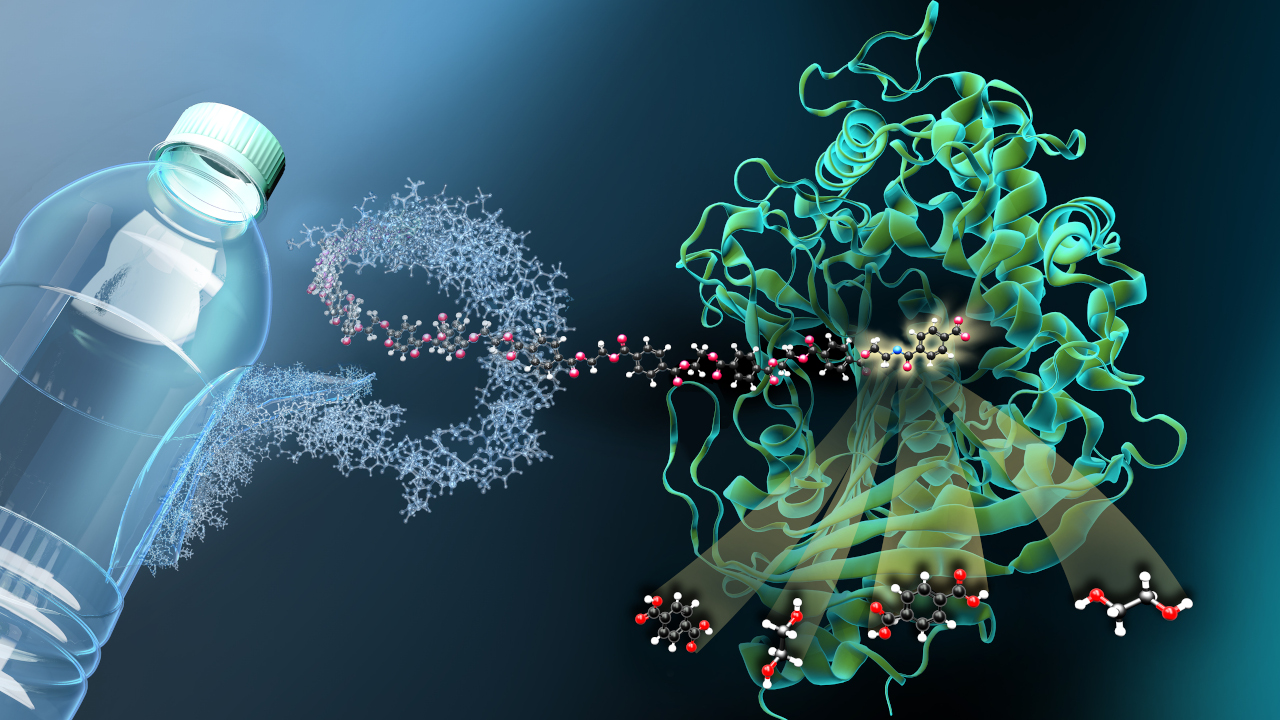

Erb and his team have already developed synthetic cycles for CO₂ fixation that are more efficient than the natural Calvin cycle - including the so-called CETCH cycle or the THETA cycle. These metabolic pathways already function reliably under laboratory conditions, but their incorporation into living organisms remains a challenge.

The researchers investigated a bacterial metabolic pathway for the conversion of formic acid. In a hybrid process, CO2 is first converted to formic acid by electrochemical reduction, which serves as a basis for growth for some bacteria. For the microbial part of the hybrid process, the team used the so-called reductive glycine pathway, the most efficient artificial metabolic pathway for carbon fixation to date.

Optimizing bacteria through laboratory evolution

The partner laboratory in Wageningen had already succeeded in integrating the reductive glycine pathway in Cupriavidus necator - a non-phototrophic bacterium that needs the Calvin cycle for CO2 fixation, but not for photosynthesis. However, it had not yet been possible to make the new metabolic pathway more efficient than the Calvin cycle.

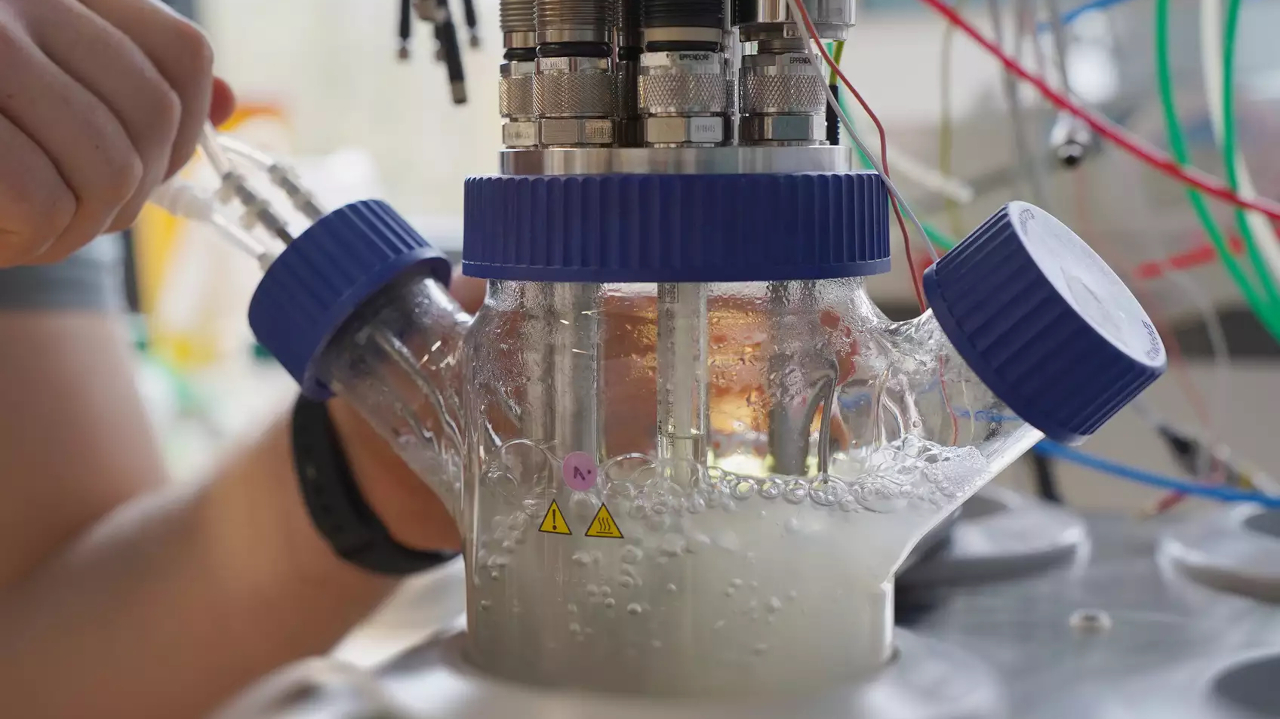

This is where Erb and his colleagues came in, having already successfully used adaptive laboratory evolution to optimize individual metabolic steps. They transferred the genes for the metabolic pathway into the bacterium using mobile DNA elements that insert themselves randomly into the genome. The bacterial cells that grew better than others were then selected. A comparison in the bioreactor showed that the artificially modified and optimized bacterial strain was able to produce significantly more biomass than the natural original strain or other comparable organisms by utilizing formic acid.

The researchers want to further accelerate the metabolic pathway through continued laboratory evolution. According to the authors, the results could make sustainable bioproduction from formic acid even more efficient and thus make the substance more usable as a chemical energy source.

chk