Intestinal bacteria produce mussel adhesive

Researchers from Berlin managed to reprogram the intestinal bacteria E. coli in such a way that they generate the underwater adhesives as seen in mussels.

Mussels produce and use one of the strongest biobased adhesives known to date, because they live in the tidal and shelf areas of the oceans and must therefore withstand strong currents and salt water. Exactly such a strong and biobased super glue would also be very useful in regenerative medicine: biocompatible adhesives could be used to treat superficial wounds, and could replace plates and screws, which are commonly used to treat bone fractures. Researchers at the Excellence Cluster UniCat (Unifying Concepts in Catalysis) in Berlin now managed to reprogram strains of the intestinal bacteria Escherichia Coli in such a way that the biological underwater adhesive of mussels can be created with help of the bacteria. As the scientists report in the journal “ChemBioChem” the new biogenic super glue and its adhesive properties can be switched on by irradiation with light.

Intestinal bacteria as a chemical factory

The extreme adhesive qualities of the mussel glue have been in the focus of research interest for quite some time. It is known that the mussel releases threads from its foot, consisting of a protein glue. The most important component of this protein glue is the amino acid 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, known as "DOPA." UniCat members Nediljko Budisa from the TU Berlin, Holger Dobbek from the HU Berlin and Andreas Möglich, now at the University of Bayreuth, have developed a new biotechnological process, with which to produce the biological underwater adhesive of mussels: "To create these mussel proteins, we use intestinal bacteria, which we reprogrammed," explains Nediljko Budisa. "They are like our chemical factory through which we produce the super glue."

Light activates adhesive properties

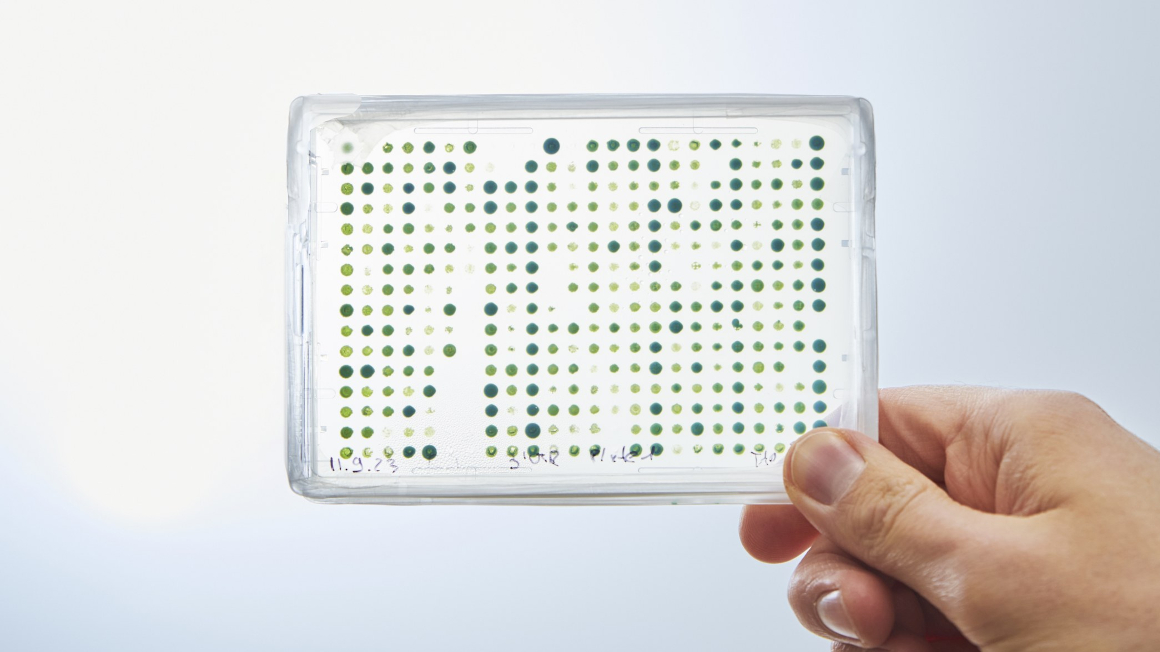

In a first step the researchers inserted a special enzyme into E. coli. Subsequently, the modified intestinal bacteria are fed with the amino acid ONB-DOPA (ortho-nitrobenzyl DOPA) as this envelops and protects the dihydroxyphenyl groups, which are responsible for the strong adhesive properties. The reprogrammed bacterium then builds these enveloped amino acids into proteins. The result: A bonding protein is obtained, whose adhesive sites are still protected. After the protein has been separated from the bacteria and purified, the protective groups are removed by means of light of a specific wavelength (365 nm). By doing so, the adhesive protein gets “activated” and can be used as a glue.

Business spin-off based on new technique

Although the adhesive properties of the mussel glue have been coveted for quite some time, and there a plenty of possible applications, thus far it was not possible to harvest it in large and homogeneous enough quantities: 10,000 mussels only provide one or two grams of the adhesive. The new technique developed by the researchers in Berlin could change all this: Two scientists from Budisa’s working group are planning to establish a business spin-off. "This strategy offers new ways to produce DOPA-based wet adhesives for use in industry and biomedicine with the potential to revolutionize bone surgery and wound healing," assert Christian Schipp and Matthias Hauf. In order to bring their business idea to life, they plan to use the Inkulab, the spin-off laboratory of the Excellence Cluster UniCat at the TU Berlin.

jmr