How roots protect maize plants from drought

The domestication of maize has greatly changed the root system of the food plant. This is the conclusion of a study involving researchers from Bonn. They also identified a gene that is crucial for the breeding of drought-resistant plants.

The cultivation of maize has a long tradition. 9,000 years ago in southern Mexico, the tastiest and highest-yielding maize plants were selected from the descendants of the original teosinte variety and used for breeding. Over the centuries, the plant has adapted to a wide variety of locations and gradually changed more than just the appearance of the cobs. The modern maize plant also produces higher yields. Until now, it was unclear how the domestication of today's most important food crop has affected the root system. An international study involving researchers from the Institute of Crop Sciences and Resource Conservation (INRES) at the University of Bonn has now closed this gap in knowledge.

Root system of 9,000 maize and 170 teosinte varieties analysed

In order to investigate the development of the roots, around 9,000 maize and 170 teosinte varieties have been analysed over the past eight years. The seeds were placed on a special brown paper, rolled and placed upright in narrow beakers. "About 14 days after germination, we unroll the paper and can then follow the growth of the early roots without disturbing soil adhesions," reports INRES researcher Frank Hochholdinger. The root growth of the maize plants in the soil was also analysed using magnetic resonance imaging, which is primarily used in medicine. Here, the Bonn team worked together with a team from the Jülich Research Centre.

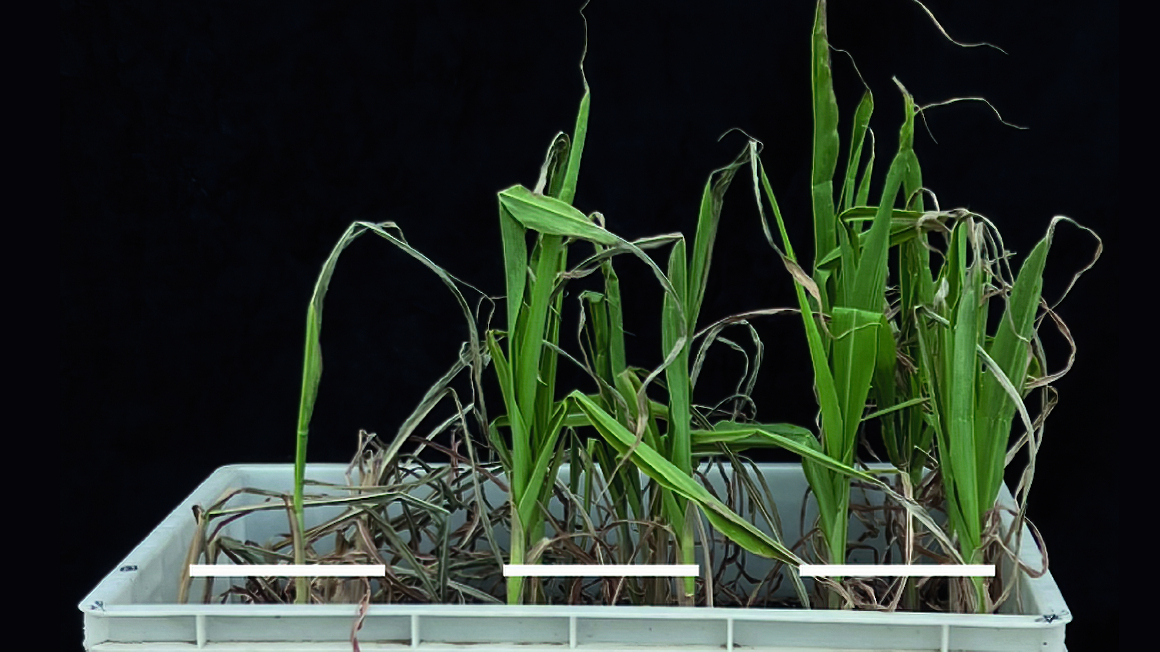

The investigations revealed the extent to which the roots of the maize plant have changed over the centuries as a result of domestication. "In maize, we often find so-called seminal roots shortly after germination - ten or more in some varieties. This is not the case with teosinte," reports Peng Yu, Emmy Noether group leader at INRES, who has since accepted a professorship at the Technical University of Munich.

Maize varieties in dry regions have more lateral roots

Under optimal conditions, seminal roots can ensure that the seedling draws large quantities of nutrients from the soil very quickly. However, as the team writes in the scientific journal "Nature Genetics", this process is at the expense of the so-called lateral roots. The formation of this type of root is impaired and water uptake is made more difficult. This is because the lateral roots increase the root surface area of the plant and thus also the water uptake. According to the researchers, the number of seminal roots varied greatly depending on the variety: varieties that are adapted to dry areas form significantly fewer seminal roots and more lateral roots. In the past, breeders had unknowingly selected for this root structure when further developing these varieties, they say.

Gene for drought-tolerant species identified

As part of the study, the researchers also investigated which genes are responsible for the formation of seminal roots. They were able to identify more than 160 candidate genes. The gene labelled ZmHb77 was examined in more detail. "We found that plants with this gene formed more seminal roots and fewer lateral roots," says Hochholdinger. According to the study, if this gene was specifically switched off, the root structure changed and the maize plant coped much better with periods of drought. "The corresponding gene is therefore interesting for the production of drought-tolerant species. In view of climate change, these are becoming increasingly important if we don't want to suffer more crop failures in the future," emphasises Hochholdinger.

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation, among others. Researchers from 20 research groups from Germany, China, the USA, Spain, Italy and Belgium were involved.

bb