Deep-sea microbes break down petroleum components

Archaea decompose alkanes from petroleum naturally produced near hydrothermal vents on the seafloor.

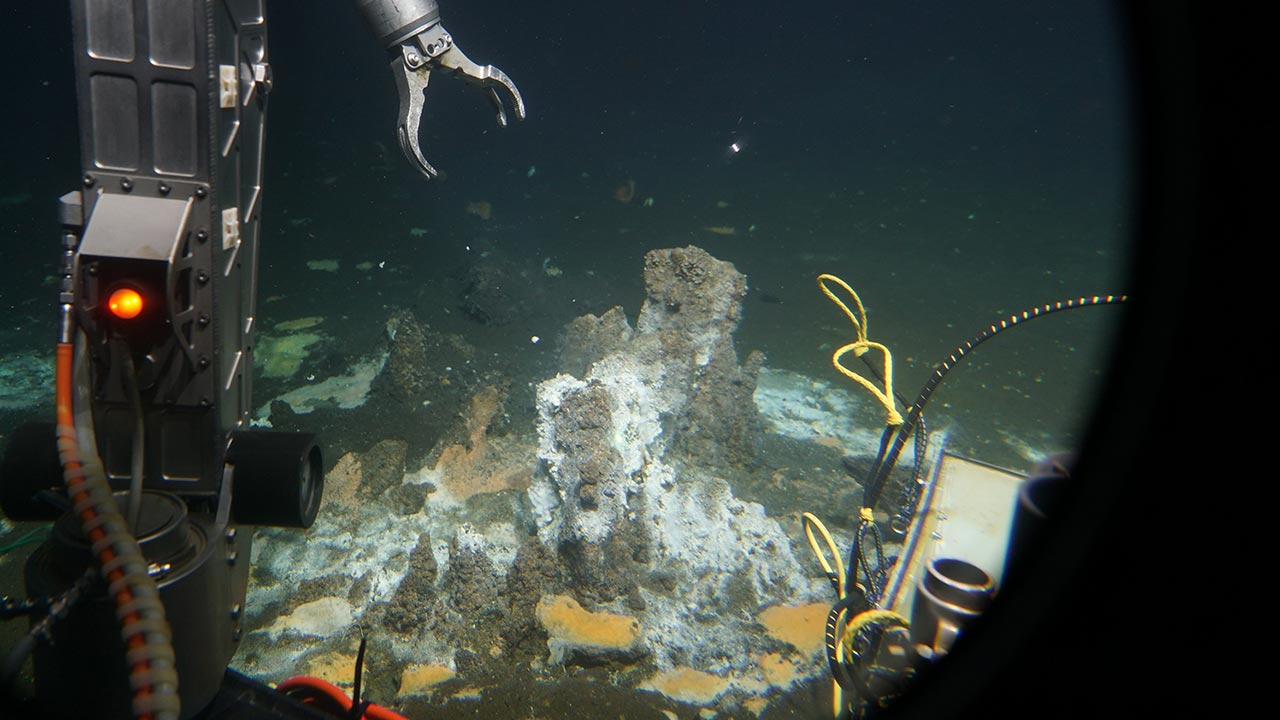

Hydrothermal vents are among the few places where there is sufficient energy in the deep sea to support life. Forms of this energy are crude oil and natural gas, which are formed from deposited organic material by the high heat from the Earth's interior. A team of researchers from Bremen has now been able to demonstrate that microorganisms indigenous to hydrothermal vents use the alkanes contained in petroleum as a food source. Until now, it was only assumed that certain microbes are capable of degrading alkanes in an oxygen-free environment.

Alkane degradation without oxygen is teamwork

In the journal Nature Microbiology, experts from MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen and the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen report on their discovery. The team succeeded in cultivating deep-sea microbes from the sediment of the 2,000-meter-deep Guyamas Basin in the Gulf of California, according to the paper. The conditions were similar to those of hydrothermal vents: at 70 degrees Celsius, with liquid alkanes but no oxygen. This showed that alkane degradation in the absence of oxygen is teamwork.

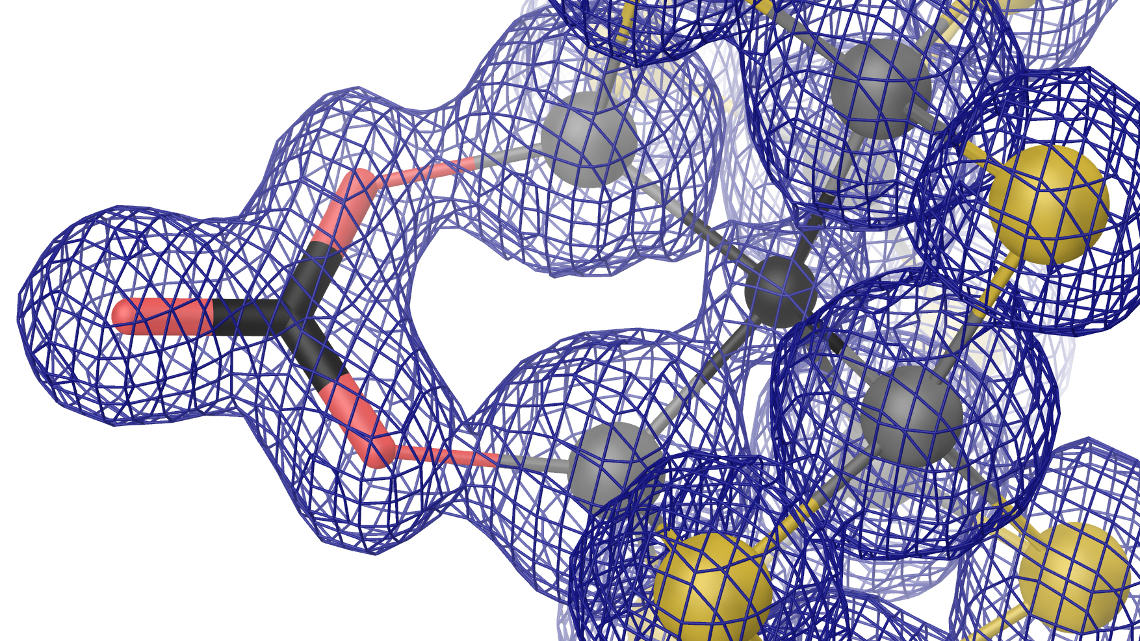

In recent years, there had already been growing evidence that certain archaea can use alkanes for their metabolism with the help of the enzyme methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR) even in the absence of oxygen. Indeed, using DNA and RNA samples, the Bremen team was able to demonstrate that the alkane degradation in their experiment is carried out by archaea of the genus Candidatus Alkanophaga. However, they can't do it alone: The part of the chemical reaction that replaces the role of oxygen is carried out by bacteria of the genus Thermodesulfobacterium. They live in close contact with the archaea.

Residual oil remains in the seabed

"Thanks to their abilities, Alkanophaga and their relatives target hydrocarbons in oil reservoirs. The remaining oil progressively solidifies and thus remains in the seafloor," explains Gunter Wegener, lead author of the study. "We have not yet been able to explore deep oil reservoirs - but the archaea are certainly disrupting the petroleum industry by doing so. But they also make an important contribution to ensuring that natural oil spills are rare."

The liquid alkanes contained in crude oil are toxic and one of the many environmental problems following oil tanker or drilling platform accidents. While some bacteria can break down alkanes near the water's surface with the help of oxygen, the oil quickly sinks into the depths and thus into oxygen-poor regions of the sea. This is where the process now detected could play a role in oil degradation.

bl