Many people suffer from food allergies. According to estimates by the German Allergy and Asthma Association (DAAB), around six million children and adults are affected in Germany alone. Peanut allergy is particularly widespread. So far, allergy sufferers have had to do without allergy-causing foods such as peanuts or mustard, as the condition cannot yet be cured. Researchers led by Thomas Reinard of Leibniz Universität Hannover are now pursuing a new approach: they want to reduce, alter or even switch off the responsible storage proteins in allergy-inducing food plants in order to reduce the risk of an immune reaction.

The joint project LACoP (Low Allergen Containing Plants) is coordinated by Leibniz Universität Hannover and funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research with a total of 778,000 euros from 2017 to 2020. In addition to plant geneticists and horticultural scientists from Hanover, the project also involves biotechnologists from Braunschweig Technical University (TU), paediatric allergists from Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin and, as industrial partners, the company Diagnostic Systems and Technologies (DST) and the German Allergy and Asthma Association (DAAB) as patient representatives.

Changing genes in storage proteins

The aim of the project is to produce hypoallergenic food plants - plants with a reduced allergenic potential. The researchers are concentrating not only on the storage protein Ara h 1 of peanuts, but also on the allergenic protein Bra j 1 in mustard. In both species, the researchers hope to use modern genome editing methods to specifically modify or cut out the genes of the corresponding proteins.

Developing antibody-based tests

The plants without allergens must be tested naturally. "The need for our own tests led to the idea of developing a test system that could be used by allergy sufferers or doctors," explains project coordinator Reinard. The result would be an analysis tool based on recombinant antibodies that are produced by project partners at Braunschweig Technical University. With the help of this tool, it would then be possible to precisely determine whether food is compatible or not with peanut or mustard allergy sufferers. Thomas Reinard's research group uses duckweed to produce the allergens required for the development of antibody-based tests.

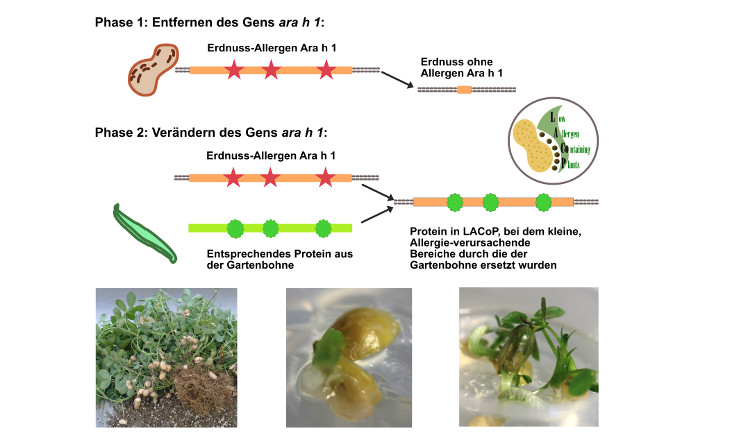

Upper panel: Phase 1: Gene Ara h 1 is completely removed by genome editing; Phase 2: small parts of the gene from the peanut is replaced by the corresponding parts from the non-allergenic garden bean.

Lower panel: Peanut plant with peanuts, which was in the soil for some time (left), small pieces of tissue and new peanut plant (right).

Mixed protein from peanut and garden bean

"In the first phase of the project, the genes are to be completely removed from the plants using genome editing, and then it will be possible to determine whether these allergen-reduced plants are still able to produce tasty peanuts at all," explains Reinard. Therefore, a second strategy is being pursued in parallel in which the allergen is not completely removed (see figure). Instead, only those parts of the protein that are directly responsible for the allergic reaction are removed. Such regions are to be replaced with corresponding regions from other plants – specifically from the garden bean – that do not cause allergies. According to Reinard, such plants would contain a mixed protein of peanut and garden bean, which should exhibit reduced allergenicity.

To do this, the regions responsible for the allergy in the protein must first be identified. These were already identified in the 1990s, but without taking the overall structure of the protein into account. This was not possible at that time. With today's methods, however, individual areas can be substituted while taking into account their effect on the overall structure of the protein. "Like when swapping Lego bricks in a corresponding model", this results in a slightly modified structure of the Lego model, as Reinard explains. These modified proteins are then analyzed bit by bit with the antibodies of the TU and the patient sera of the Berlin Charitè.

Producing new proteins with modern techniques

Initial analyses already show that the data from the 1990s are not so accurate and cannot be confirmed with the modern and much more detailed procedures used today. "This has come as a big surprise. Now we are doing basic research and are using modern techniques and a newly developed method to produce these proteins," said the plant geneticist.

However, the cultivation of allergen-reduced peanuts is still a long way off. "In order to produce such a plant, the genome of a cell must first be altered using genome editing. However, the restoration of an entire plant from this very cell is much more complex. This so-called regeneration is difficult with peanuts and can take up to a year. For this reason, the consortium has chosen an allergen made from mustard as its second main pillar, as the regeneration works faster here and at higher rates. However, in contrast to southern France, there are very few people in Germany who are allergic to mustard, which makes it difficult to obtain the sera required for the analyses.

Hyperallergenic plants as medicine

No large-scale cultivation is currently planned for either plant species in the field – partly because the European Court of Justice has classified modified plants as genetically modified organisms (GMOs) by means of genome editing – they are therefore subject to the strict regulations of the GMO Directive. For this reason, the researchers are also focusing on the use of hypoallergenic plants as medicines.

Specifically, they intend to use them in so-called oral immunotherapy. This involves increasing doses of peanut protein to stimulate the immune system in order to hyposensitize those affected. "Here too, a peanut that is less allergenic is helpful because the risk of allergic reactions is significantly reduced." Much fewer plants are needed for such an application, which "could be cultivated in a closed greenhouse," explains the researcher.

Joint project LACoP:

Project coordinator:

Leibniz-University Hanover, Institute of Plant Genetics; production of allergens and editing of genomes

Project partners and their responsibilities:

Leibniz-University Hanover, Institute for Horticultural Production Systems; Regeneration of genome-edited plants

Technical University of Braunschweig, Institute of Biochemistry, Biotechnology and Bioinformatics; Production of recombinant antibodies

Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Clinic for Pediatrics m.S. Pneumology and Immunology and Intensive Care Medicine; Tests with blood sera of allergy patients

DST Diagnostic systems and technologies; development of test systems, production of (modified) allergens

Deutscher Allergie- und Asthmabund e.V. (German Allergy and Asthma Association); patient representation analyses the needs and acceptance of patients

Detecting peanut content in foods

A further objective of the LACoP consortium is to provide physicians and the food industry with test kits that can be used to determine the content of critical allergenic proteins in food simply, cheaply and accurately. It is also possible to detect "peanut residues" that can enter the production chain at various points, which offers peanut allergy sufferers additional protection. "We want to try to better detect allergen contamination in the food production process so that contamination can be ruled out for allergy sufferers," explains project coordinator Dr. Reinard.

Autorin: Beatrix Boldt