They say two is better than one. But is that also true in plant protection? A team at Anhalt University of Applied Sciences (HSA) looked into this question. The scientists had discovered that certain plant extracts and beneficial microorganisms can protect crops against fungal diseases. ‘So we asked ourselves: what if we combined the two?’ explains agricultural scientist Marit Gillmeister. This led to the KombiAktiv2 project, funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and headed by Prof. Ingo Schellenberg from HSA in Bernburg. The Leibniz Institute for Vegetable and Ornamental Crops (IGZ) in Großbeeren was brought on board as a partner in the project. It contributed the necessary expertise on plant-microorganism interactions in horticultural crops.

In her doctoral thesis, Gillmeister had previously been able to prove that plant extracts from rhubarb root in particular are effective against various fungal pathogens in agriculture. Rhubarb contains many polyphenolic compounds such as stilbenes and flavonoids, which in combination make the extract particularly suitable.

In addition, researchers from HSA and IGZ were able to show that certain symbiotic fungi and bacteria are both directly active against pathogenic fungi in the root zone and, in interaction with the plant, induce or support its own defence mechanisms.

Asparagus cultivation requires sustainable protection against fungal diseases

‘We chose asparagus and basil for the project because there are no suitable methods available for controlling fungal pathogens that cause root rot in either crop,’ reports Gillmeister. Fusarium species are a major problem in asparagus cultivation because the plant is perennial. Initially, in the second to third year of cultivation, the fungal pests cause significantly weaker plant growth and more and more gaps in the crop, and the pathogens accumulate in the soil. Over time, the soil becomes so contaminated that the area can no longer be planted with asparagus without problems. However, suitable alternative areas are often lacking.

The first important question in the project was: Are the two approaches even compatible? ‘If the rhubarb root extract inhibited the beneficial microorganisms, that would of course have been a knockout criterion,’ says the agricultural researcher. However, investigations quickly showed that this was not the case at all.

The team also had to ensure that the extract and the root-symbiotic microorganisms also inhibit relevant soil-borne pathogens in asparagus and basil – in this case Fusarium species. ‘In laboratory tests, we found that it had a good inhibitory effect,’ says Gillmeister. So it was time for a field trial. A practical partner was found in the Winkelmann asparagus farm in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the company Agraforum supported the project from an economic perspective.

Practical field testing takes time

In the first field trial, the researchers immersed the root balls of annual asparagus plants in suspensions of rhubarb root extract or microorganisms, as well as a combination of both, prior to planting. The microbial suspension contained both fungi of the genus Trichoderma and bacteria of the genus Bacillus – certain isolates of both genera are known to colonise the root zone of plants and exert beneficial effects there. The team proceeded in a similar manner in the second field trial. Here, however, the researchers used young plants, which were also dipped in the suspensions before planting and later watered with them again.

‘Over the course of the project, we regularly took root and soil samples to check whether the microorganisms had established themselves well in the root zone,’ explains Gillmeister. In fact, all relevant strains were detectable in sufficient density even over the winter. Sufficient colonisation of the rhizosphere and the soil influenced by the roots with beneficial microorganisms is a prerequisite for them to interact successfully with the plant and protect it from fungal pests.

Due to the short project duration of two years, the team has not yet been able to detect any differences in growth or the occurrence of disease symptoms when comparing the treated plants with the control plants. ‘The asparagus plants from the first field trial were not harvested until this year, after the end of the project,’ the researcher regrets. However, the asparagus farm will continue to monitor the trial plots. ‘The next two years will show whether the treatments were successful,’ Gillmeister is confident. If the treatments prove successful, the proposed method will provide a good basis for further research.

Mixed results, but interesting potential

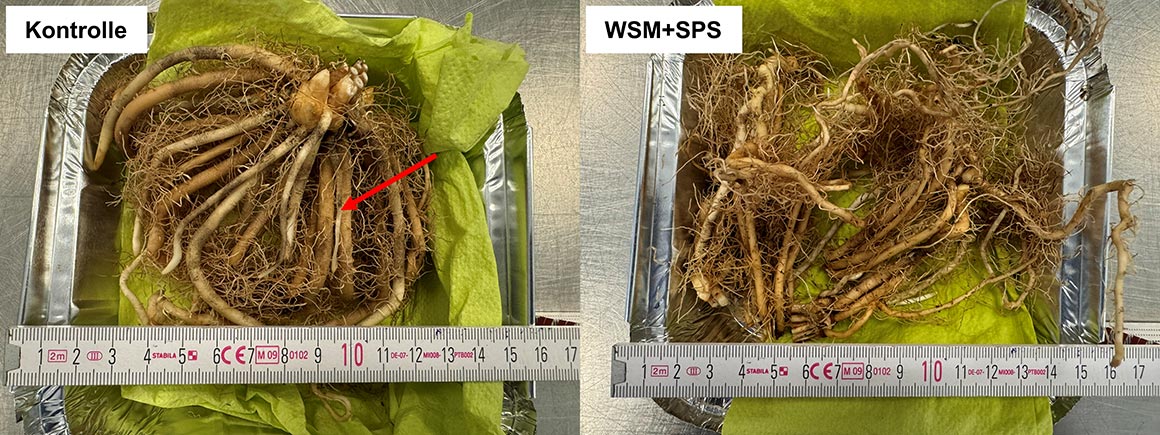

Initial positive results have already been achieved in parallel pot trials. In asparagus, but also in basil, no toxic damage to the leaves was observed when the plants were treated with rhubarb extract. ‘This is also a fundamental prerequisite for further work,’ says Gillmeister. The most promising results were obtained in pot trials with young asparagus plants: When an asparagus plant is attacked by soil-borne harmful fungi, this is evident from leached or lysed roots. ‘This was observed in the untreated control plants,’ reports Gillmeister. In contrast, the plants that were treated individually or in combination showed significantly less root damage.

However, no disease-suppressing effect was found in the pot experiments with basil, neither through the microorganisms, nor through the extract, nor through a combination of both. ‘Instead, we observed increased plant growth as a side effect,’ says Gillmeister, ‘according to the economic experts at Agraforum GmbH, this is an approach to strengthening plants that could be pursued further.’

The bottom line is that there is sufficient evidence, particularly with regard to the use of root-symbiotic microorganisms, to pursue this approach in a more in-depth project. ‘Two years is simply too short a period to obtain meaningful results, especially with a perennial crop such as asparagus,’ concludes Gillmeister.

Author: Björn Lohmann

The KombiAktiv2 project

KombiAktiv2 stands for ‘Combined use of bioactive secondary plant compounds and root-symbiotic microorganisms for biological control of diseases in horticultural crops’. The joint project between Anhalt University of Applied Sciences and the Leibniz Institute of Vegetable and Ornamental Crops ran from October 2022 to December 2024 and was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research with €374,595.