New yeast isolated from tree sap

Braunschweig researchers have discovered a new species of cold-loving yeasts in tree sap.

Tree sap contains important ingredients for food or pharmaceutical industry. Besides minerals and nutrients, it is the microorganisms, especially yeasts, that make the sugar-rich sap interesting for biotechnologists. These yeasts produce important enzymes such as lipases, which digest fat, or plant substances such as the carotenoid astaxanthin. Astaxanthin is extracted from the tree yeast Phaffia rhodozyma, for example, and used as an additive in fish feed, which later gives the salmon its distinctive color.

Cold-loving yeasts grow in domestic tree sap

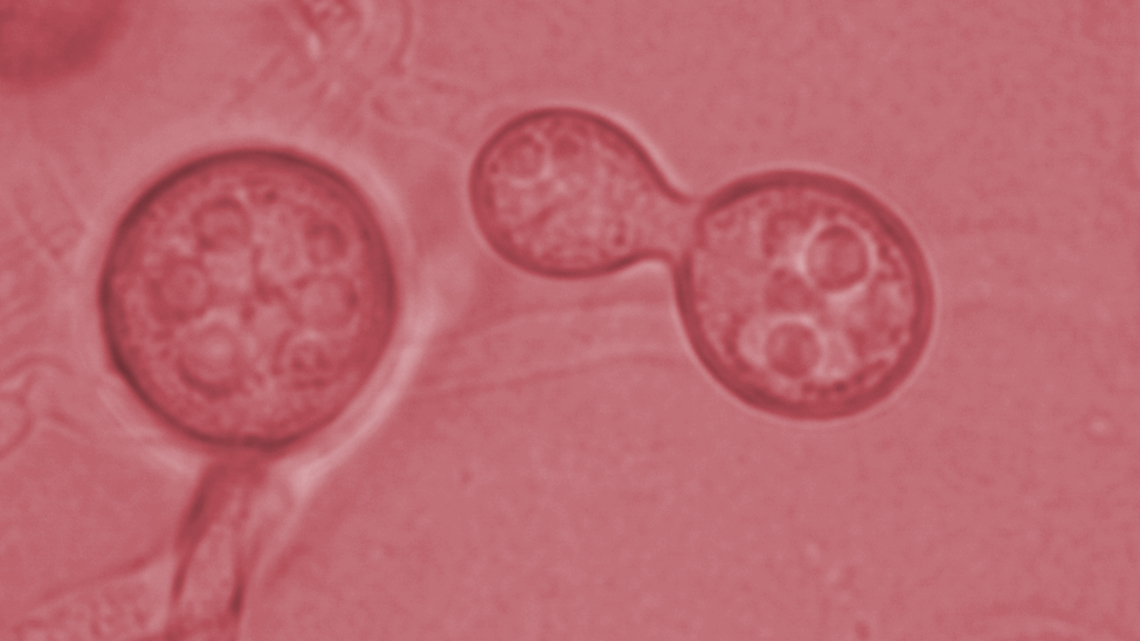

Microbiologist Andrey M. Yurkov from the Leibniz Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ) has now discovered a new yeast species in Braunschweig. While taking samples of sap from native trees such as birch, beech, hornbeam and dogwood, he unexpectedly came across a yeast fungus of the genus Mrakia. "Mrakia fibulata is the first of these yeasts to grow at a temperature of more than 20°C," emphasizes Yurkov, who published his research in a Springer Nature paper.

Yeasts of the Mrakia genus actually prefer colder habitats such as glaciers, ice and permafrost. But climate change is having a major impact on these regions. The Calderone Glacier in southern Europe, where the yeast species has also been found, has been melting for years. Scientists expect that the glacier in the Italian Abruzzo region will soon disappear completely - and with it the habitat for the cold-loving tree yeasts.

Mrakia survives despite climate change

Yurkov is all the more pleased that these yeasts could now be detected "in moderate-climate Braunschweig". "It is particularly interesting that cold-loving microorganisms such as the newly discovered Mrakia fibulata as well as some related species have so far managed to survive climate change in Central Europe. This gives us reason for hope that they will continue to exist in nature, not just in bioresource collections such as the DSMZ."

bb/um