How bacteria and algae talk

Pseudomonas bacteria can immobilise microalgae within moments. Researchers from Jena identified orfamid A as the chemical culprit.

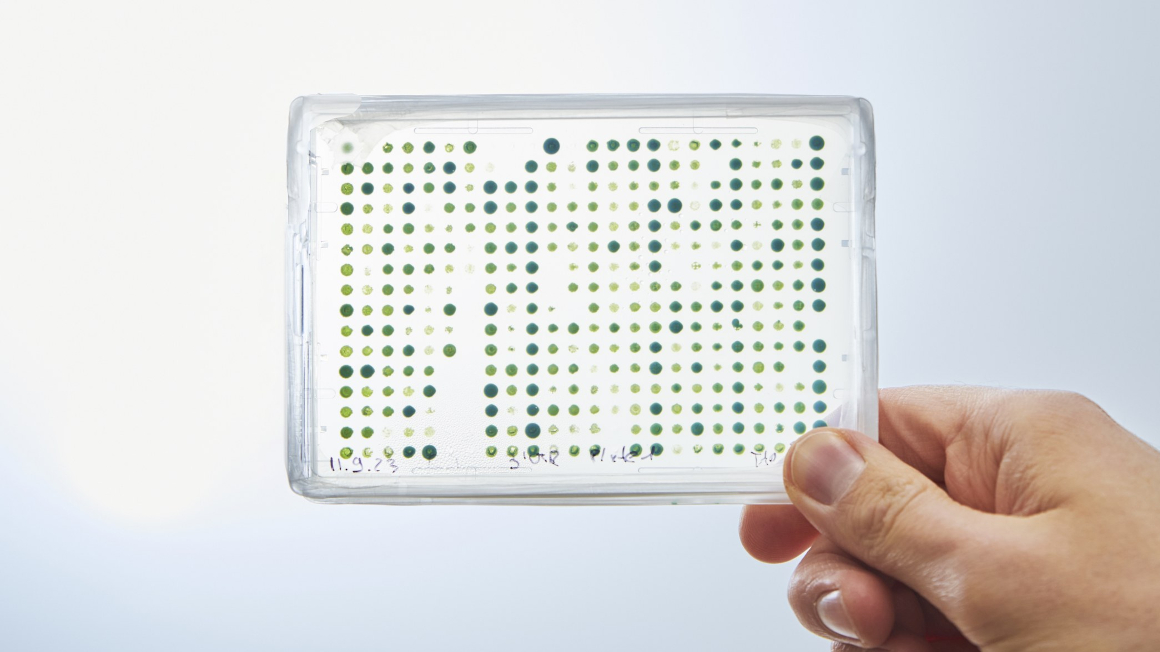

Microbes often live in complex biosystems. Their co-habitation is regulated by a number of chemical signals. Researchers from Jena now identified the mechanism that causes Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, roughly ten micrometer in size, to lose their flagella within minutes of coming close to Pseudomonas protegens bacteria, which are merely two micrometers in size. According to their published results in the journal „Nature Communications“, the authors identified the lipopeptide orfamide A, released by the bacteria, as the culprit disturbing the cell membrane of the algae.

Understanding microbial community structures

The green algae species Chlamydomonas reinhardtii are approximately ten micrometers in size, have two flagella with which they swim around, and are photosynthetic microorganisms (phytoplankton) that contribute about 50% towards fixing the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide and, as a by-product of photosynthesis, they supply the oxygen that is essential for our survival. In addition, microalgae, which are found in fresh water, wet soils or the world’s seas and oceans, represent an important base for food chains, especially in aquatic systems. However, if they come too close to the Pseudomonas protegens bacteria, their fate is sealed: within minutes they lose their flagella, and they can no longer move nor propagate. An interdisciplinary team of researchers headed by Maria Mittag and Severin Sasso at the at Friedrich Schiller University, Jena (FSU), and Christian Hertweck at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology – Hans Knöll Institute (HKI) investigated this complex interplay: “We want to understand the mechanisms through which the microbial community structures are formed and their diversity maintained,” says Hertweck.

Opening of calcium channels causes loss of flagella

If both bacteria and algae are in the same vicinity, the bacteria surround the algae – and within 90 seconds the algae will have lost their flagella. Researchers from Jena now identified the underlying mechanism: Orfamide A, a cyclical lipopeptide, which the bacteria release together with other chemical compounds. “Our results indicate that orfamide A affects channels in the cell membrane, which leads to these channels opening,” explains Severin Sasso. “This leads to an influx of calcium ions from the environment into the cell interior of the algae.” A rapid change in the concentration of calcium ions is a common alarm signal for many cell types, which regulates a large number of metabolic pathways.

In addition, the teams were able to show that the bacteria can tap the algae and use them as a nutrient source if they are lacking in nutrients. “We have evidence that other substances from the toxic cocktail released by the bacteria also play a role in this,” says Maria Mittag.

jmr