Berlin: Industrial biotechnology meets foodtech

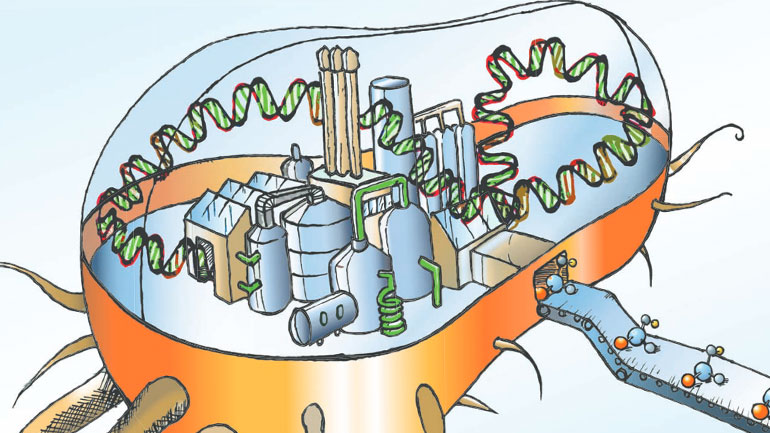

At a conference organised by the industry association Weiße Biotechnologie e.V. (IWBio) in Berlin, stakeholders discussed the potential and innovation obstacles of biotechnological alternatives to meat, milk and egg products.

The figures speak for themselves: In 2022, Germany was by far the largest sales market for protein foods produced without animals, at 1.9 billion euros. Germans, who are otherwise sceptical about food innovations, are open to dairy products, fish and cheese produced using optimised microorganisms and cell-based processes. According to recent surveys, a good 60% of over-25s and almost 80% of under-25s would at least like to try them. It is not only the greater animal welfare, but also CO2 savings of 20% to 30%, 70% of agricultural land, fertiliser, pesticides, animal feed and 65% of water that make precision fermentation and cell-based alternatives attractive to many consumers in times of climate crisis.

Tapping into a market worth billions

"Acceptance is not the problem," emphasised Ivo Rzegotta from the foodtech think tank Good Food Institute at the annual workshop of the industry association Weiße Biotechnologie e.V. (IWBio) in Berlin. Even Federal Research Minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger signalled unusually clear political support in her welcoming address to the IWBio conference: "I am certain that these products [proteins from precision fermentation and cell-based protein] will revolutionise our nutrition. Biotechnology is the key to this - whether in the production of animal-free beef or [recombinant] pea protein. There is a market worth billions waiting to be tapped," said the Minister.

A good 50 industry experts from IWBio e.V. discussed in the brightly lit premises of microbial cheese and egg manufacturer Formo Bio GmbH why companies worldwide still seek product authorisation outside the EU, why they do not scale up their production in Germany and why even companies that want to stay in Germany are looking abroad.

"For many years, almost all investments were channelled to North America, but that's over now," says Rzegotta. For two years, he has been trying to make successful models from neighbouring EU countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark, Switzerland and the UK appealing to political decision-makers in Germany. "Europe is catching up, but Germany is only attracting 1.6% of investment and, despite its strong market position, is currently falling behind in a global comparison.

Slow EU authorisation procedures for novel foods

Rzegotta cites the slow EU approval process for precision fermentation and cell cultivation products covered by the EU Novel Food Regulation as one reason for this. In Singapore and the USA, this takes well under 12 months for similar quality, whereas in the EU it takes 18 to 48 months. "There is no pressure or incentive for the competent authority EFSA to work faster," revealed industry representatives on the sidelines of the bioökonomie.de conference. And when asked why the authorisation strategy of the USA and Singapore was not simply copied, the representatives of the ministries and the EU Commission present were verbose, but did not provide any concrete answers.

Instead, EU representative Adrian Leip emphasised that the Commission was very afraid of an exodus of companies from Europe and was thinking about how to speed up the approval of novel foods and reduce resistance from powerful lobby groups such as farmers' associations. "We should just be able to do it once," complained Natalia Drost, Head of Strategic Projects at Mushlabs GmbH in Hamburg, which cultivates an additive-free product range from edible mushroom mycelia, at the conference. "We've already been waiting two years with ongoing personnel costs for 35 employees."

"EU authorisation process too fear-based"

The second reason Rzegotta cites is that the EU authorisation process for novel foods is fear-based rather than opportunity-based. "After the safety of the product has been proven by data, EU representatives in the GAFF committee vote on the risk profile of the product once again in the final step before authorisation," says Rzegotta, who called for more transparency regarding the decision-making criteria in Berlin in order to put a stop to previous EU lobbying. Market authorisation that was thought to be safe could be overturned. Planning security for companies looks different.

This year, the Netherlands demonstrated how companies can be kept in the country despite EFSA bureaucracy by introducing a tasting clause. The national provision, which Switzerland and the UK intend to introduce shortly, allows manufacturers to have their product tasted by interested consumers without any red tape and thus test product acceptance before EU market authorisation and large investments are made. According to industry experts, approval takes just two weeks. "There could be something like this in Germany too," says Rzegotta.

Fermentation capacities in Germany can still be expanded

However, he also cites the lack of willingness on the part of the German government to provide public funding to support companies striving to enter the emerging billion-euro market. While the UK is investing £48 million, France €65 million, the Netherlands €60 million and Spain €12 million in scaling up microbial and cell-based protein production, the Fraunhofer ISI reports that just €3 million has been channelled to start-ups in Germany over the same period. Denmark recently became the first country to present the first plant-based protein strategy in Europe. "We need significantly more than 10 million euros and a long-term commitment from the industry to build up more fermentation capacity in Germany," explained Martin Langer, Executive Vice President and Managing Director BioScience Operations at BRAIN Biotech AG.

In individual presentations by company founders and nutrition experts as well as panel discussions, it quickly became clear that although German biotech developers currently still have sufficient scaling capacities at CDMOs such as Evonik, Corden Biochem GmbH or Wacker AG, they are hindered by the sluggish authorisation procedures, less specific and supportive framework conditions as well as tax discrimination against animal-based foods – they have to add 19 instead of 7 per cent VAT to the net price – and a conservative, biotech-sceptical marketing mindset on the part of wholesalers are driving them to apparently more fearless foreign countries.

Formo: First market authorisation sought in Singapore

Formo Bio founder and CEO Raffael Wohlgensinger explained that although his company, which was founded in 2019, is looking for ways to develop and produce in Germany, the market authorisation of the first cheese product based on bacterially produced casein will take place in Singapore in early 2024. As the money from the first EUR 42 million financing round for product development has almost been used up, the company is currently looking for new investors.

Although he really likes the European approach, he realises that governments outside Germany and Europe are much more willing to invest. Dubai, for example, has promised 100 million in equity capital and the same amount of support for scaling up production – and that is not an isolated case. "The question is, do we stay here or do we go where it's easier," says the Swiss company co-founder.

Other companies at the IWBio annual conference also explained that it is not really due to EU state aid law that innovations financed with German taxpayers' money are moving to other EU countries or being authorised outside of Europe, but rather to a lack of willingness to take risks and the bureaucratic clinging to old habits.

Hamburg-based Microharvest GmbH, which specialises in the efficient and cost-effective production of single-cell proteins and cell extracts, and Mushlabs GmbH, which focuses on fungal mycelium fermentation, left no doubt at the conference that they want to get started with production.

Nevertheless, Microharvest GmbH plans to launch its production pilot plant with a production capacity of 100 kg of single-cell protein per day in Lisbon at the end of November. "We will scale up further next year," says COO Jonathan Roberz. Hamburg-based Bluu GmbH, which is working on cell-based fish in view of 90% overfished stocks and growing microplastic pollution in the waters, plans to scale up to the 500 litre scale in Germany next year, but will allow production in Singapore.

Corden Biochem GmbH, the largest service provider with a fermentation volume of 3,000 cubic metres, also sees Germany's energy policy as a competitive disadvantage. "The rejection of all kinds of technology without offering corresponding alternatives kills innovation and reduces the long term viability of the biotechnology industry in Germany," says Managing Director Klaus Pellengahr. In France, energy costs a third less than in Germany. "In nine months' time, we will see in biotechnology what we are currently seeing in the chemical industry: the great exodus," he predicts. Andreas Löffert, Managing Director of the Straubing-Sand special-purpose association, criticises the fact that political obstacles, particularly in the responsible ministries, have more than doubled the cost of a biotech multipurpose plant, which is due to go into operation in the second quarter of 2025, to 90 million euros.

"Labelling biotech products"

Nutritionist Hannelore Daniel, former member of the Bioeconomy Council, had critical words for the industry, which endeavours to present its products as GMO-free. Irrespective of the fact that biotechnologically optimised production organisms excrete proteins into the medium and are no longer present in the end product - similar to the production of vitamins and food enzymes - and are therefore not subject to labelling in the EU: "We must clearly state that we produce with the help of biotechnology and stand by its benefits."

This is precisely because, in Daniel's view, biotech products are usually more expensive than cheap products from factory farming, as long as their immensely high environmental costs do not have to be factored in. It is true that protein products produced using biotechnology do not contain allergens, antibiotics, growth hormones and microplastics like conventional meat, fish and dairy products. However, Victoria Reinsch from Formo Bio explained that psychological advertising tricks used to promote animal products "without genetic engineering", such as showing happy families and children playing with nature, made the obviously synthetic biotech products look worse than the established cheap or high-class organic products for no factual reason. Only education and honesty as well as positive images that make innovation through biotech emotionally understandable and comprehensible can help against this.

Logistics and distribution problems

Daniel was delighted that "consumers are increasingly realising that they can participate in world events with a knife and fork. Previously, only the price was decisive. Now it's suddenly about animal welfare, health, regionality, the land required for production and climate protection." However, she also criticised the protein hype and used figures on protein demand to show that although the world's hunger for protein is increasing, there is no shortage of protein, just a logistics and distribution problem - and that micronutrients, calories and fats should not be lost sight of.

Even if animal protein were fully replaced by protein alternatives, the potential savings in CO2 emissions would be a maximum of 20 to 30 per cent. She also made it clear that although there is a lot of talk in Germany about a nutritional turnaround, this means that nuts, pulses and vegetables have to be imported and no one has yet answered where from. A healthy diet requires twice as many vegetables, three times as many pulses and four times as many nuts as are produced in Germany.

At the conference, the proposal by BMBF speaker Enrico Barsch to seek cooperation with the Federal Ministry of Economics in order to establish appropriate rules to promote technology transfer and the commercialisation of R&D in the foodtech sector was welcomed. Langer believes that this sector is still not prioritised enough in terms of its CO2 reduction potential. Of the USD 2.4 trillion invested in climate protection in the USA between 2010 and 2021, just USD 14.2 billion has been channelled into the field of precision fermentation and cell-based protein production. "An imbalance when you consider how biotechnological methods could help to reduce animal-based CO2 emissions," says Langer.

Thomas Gabrielczyk