Mussels with many partners

Deep-sea mussels enter into symbioses with a large number of bacteria and are thus well prepared for changing environmental conditions.

Many cooks spoil the broth? Deep-sea mussels follow a different principle. They form symbioses with an unexpectedly large number of bacterial strains. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen and the University of Vienna suspect that what at first glance seems to contradict previous assumptions in evolutionary biology could actually be a widespread principle.

Bacteria provide nutrients

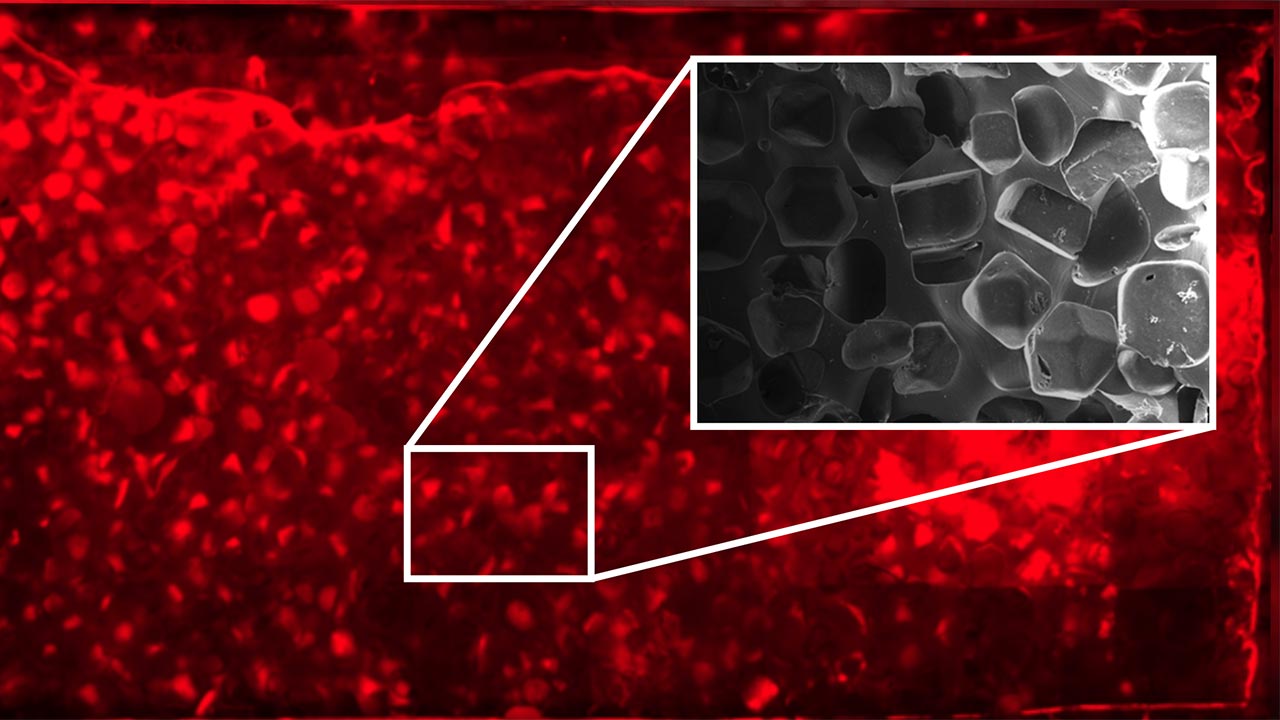

On several research trips to black smokers, hydrothermal vents of the deep sea, the scientists have collected Bathymodiolus mussels, which are distant relatives of the blue mussels. The biologists then analyzed which bacteria live in the gills of the mussels and sequenced their genomes. These microorganisms live in symbiosis with the mussels: While the bacteria, for example, convert substances that the mussels cannot use into valuable nutrients for them, the mussels offer the bacteria a safe habitat within the nutrient-rich hot springs.

Prepared for all eventualities

The researchers had expected to find one or two symbiotic strains in the gills. In the journal "Nature Microbiology", however, they reported that up to 16 symbiotic bacterial strains live in the gills of each mussel. They fulfill different functions, help with different metabolic conversions and have different abilities. “Different symbionts can, for example, use different substances and energy sources from the surrounding water to feed the mussel,” explains Max Planck researcher Rebecca Ansorge. Others are particularly resistant to viruses or parasites. Depending on the environmental conditions, one strain can dominate the other. The mussel can therefore adapt quickly, even if the conditions in the black smoker change or the mussel changes its location.

Special form of symbiosis

The large number of symbionts surprised the researchers above all because symbiotic bacterial strains usually compete for the nutrients supplied by the partner. However, since the mussels apparently only provide the habitat and the bacteria feed on the nutrient-rich surrounding water, the different strains can coexist, even if the conditions for individual strains are less favorable.

"Next, we want to investigate whether this diversity also exists in other deep-sea symbioses, for example in sponges or clams," explains Ansorge. "We also want to examine if our observations are typical for symbioses or if they also occur in closely related free-living bacteria, which are very common in the oceans."

bl/um