Measuring shelf life with infrared light

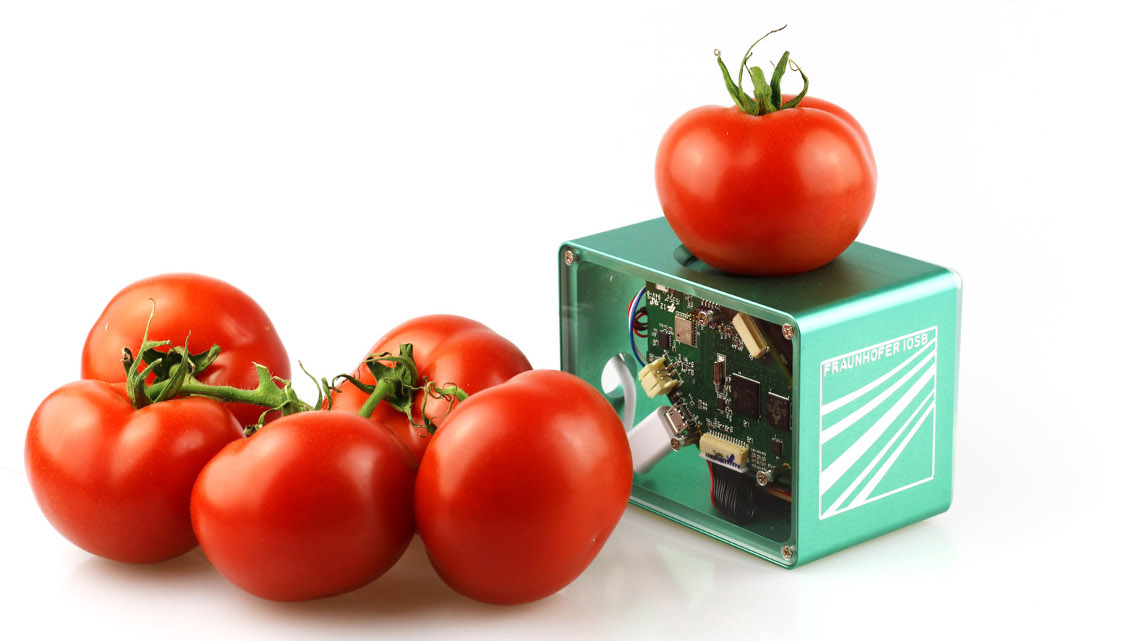

Fraunhofer physicists have developed a pocket-sized food scanner that uses infrared light and intelligent algorithms to determine the shelf life of food.

In light of the growing world population and dwindling resources, we can no longer afford to simply throw away food. And yet, according to a study by the environmental foundation WWF Germany, ten million tons of food end up in Germany's garbage every year - often for fear of spoiled goods. However, many foods are edible for much longer than the best-before date suggests. To limit this wasteful behaviour, Fraunhofer researchers have developed a pocket-sized food scanner that detects whether food is spoiled. A test phase in supermarkets is planned for early 2019: This will also include the question whether and how consumers will accept the device.

17 measures to combat food waste

Of the 10 million tons of wasted food in Germany, about 1.3 million tons are thrown out every year just in Bavaria. Therefore, the Bavarian State Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Forestry aims to counteract this waste with a total of 17 measures. These include the food scanner, which was developed by researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Optronics, Systems Engineering and Image Evaluation IOSB, the Fraunhofer Institute for Process Engineering and Packaging IVV, the Deggendorf Institute of Technology and the Weihenstephan-Triesdorf University of Applied Sciences.

Infrared light measures composition

This scanner uses a near infrared (NIR) sensor to determine the freshness of food - whether it's packaged or not - as well as which and how many ingredients each product contains. "Infrared light is beamed with high precision at the product to be investigated and then the scanner measures the spectrum of the reflected light. The absorbed wavelengths allow us to make inferences about the chemical compossition of the product," explains Robin Gruna, project manager and scientist at Fraunhofer IOSB. A further advantage is that the scanner can also be used to detect counterfeit foods, for example when rainbow trout is sold as salmon or olive oil is mixed with other oils. But the infrared scanner has its limits: according to the manufacturers, only homogeneous food can be detected. Heterogeneous products, i.e. products with many different ingredients, cannot be analysed with this method.

Intelligent algorithms detect degree of freshness

In addition, the scientists have developed intelligent algorithms that recognize what the infrared sensors have measured. Using tomatoes and minced meat as examples, Gruna's team "trained" the algorithms. Using statistical methods, the infrared spectra of ground beef were correlated with microbial development and the further shelf life of the meat was extrapolated. The scanner then sends the measured data for analysis via Bluetooth to a specially developed cloud-based database in which the evaluation procedures are stored. The measurement results are then transferred to an app, which displays the results to the consumer and shows how long the food can still be stored under the respective storage conditions or whether it has already been spoiled. In addition, the app also provides information on how the food can be used alternatively, if indeed it has been stored for too long.

The developers aim for a broad deployment of the scanner and app along the value chain to reduce possible losses and food waste. Moreover, their set-up might also be useful outside the food industry. For example, the system could be used to distinguish and classify plastics, wood, textiles and minerals. "The range of potential applications is very wide; the device just needs to be trained accordingly," says Gruna.

jmr