What makes pollen stick

Materials researchers at the University of Kiel have measured how strongly pollen adheres to certain flower organs.

Late summer is the time of the catsear, a herb that is often confused with the dandelion. Hypochaeris radicata, as botanists say, blooms bright yellow until late fall. Researchers from the University of Kiel have now taken a closer look at the journey of the herb's pollen and analyzed how it adheres at the various stations of its journey.

"If pollen is transported by insects from flower to flower, it encounters three different types of surfaces to which it must attach itself and then detach again. We want to find out which adhesive mechanisms enable this," explains the bionic Stanislav Gorb. The team's findings to date have been published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, suggesting unexpected complexity.

Pollenkitt can weaken adhesion

The common assumption had been that the so-called pollenkitt, an oily substance covering the pollen, has a central adhesive function. The new study, using the example of common catsear, has now shown that under certain conditions the pollenkitt has the opposite function, i.e. it cancels adhesion. In fact, in addition to the pollenkitt, several factors determine the strength of the adhesion: the humidity, the age of the pollen and the nature of the adhesion surface. "We must consider the adhesive mechanisms in a much more differentiated manner", Gorb sums up.

Adhesion to the stigma much stronger than to the style

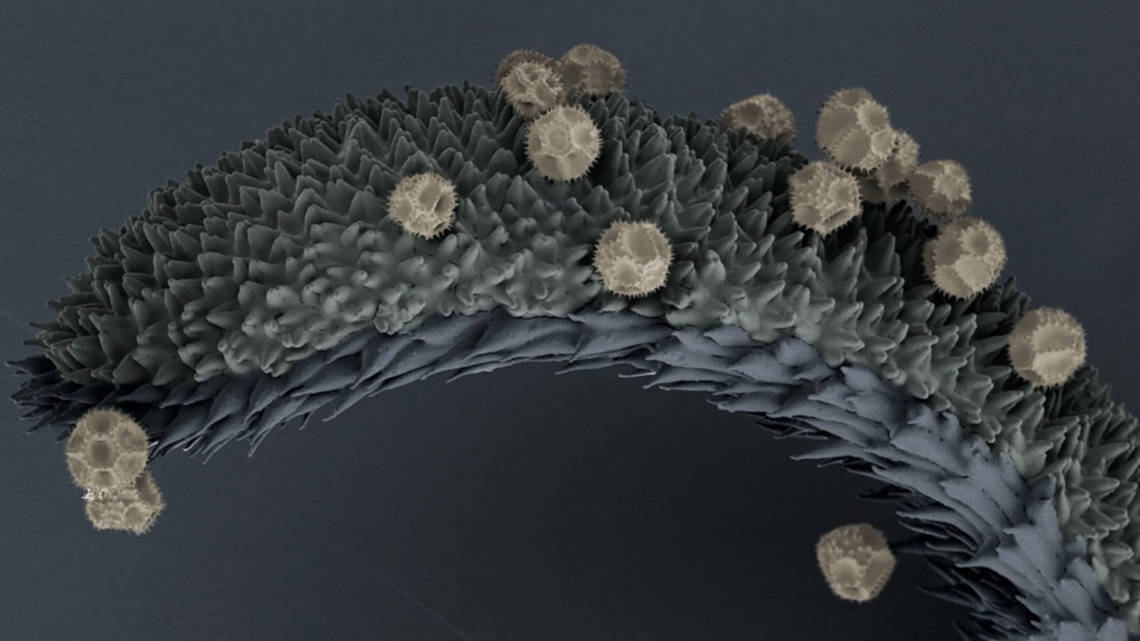

The researchers used an atomic force microscope to measure how strong the respective adhesion is. On the stigma, the female organ on which the insects deposit the pollen collected in other flowers, the pollen adheres more than four times as strongly as on the style, the male part of the flower from which it is detached and collected by insects. In this way, the plant ensures that only its own pollen travels with the insects and that foreign pollen successfully pollinates its own flowers. "We assume that during the course of evolution, the two parts of the plant have developed different functions, in order to optimize the pollination process," interprets the material scientist Shuto Ito. "The newly found pollen gripping mechanism on the stigma is likely to assure the reproduction of plants by anchoring pollen on the stigma until fertilization occurs."

Possible insights for chemistry and medicine

The researchers suspect the difference in the adhesion of the two flower components in the microstructure of their surfaces. "If we can discover the mechanisms by which such interactions of microparticles and surfaces could be controlled, we could potentially draw conclusions for coating and printing processes, the transport of medicinal substances, or the treatment of respiratory diseases," hopes Gorb.

bl/um