Rust-eating microbe found in Twentekanaal

So it exists after all: the microbe that eats both rust and methane. After a long search, Max-Planck researchers in Bremen have found such a multi-talent.

The researchers' report on their discovery in the 'PNAS' specialist journal. In addition to carbon dioxide, methane is a climate killer that presents a long-term threat to life on earth. However, for many terrestrial and marine microorganisms this greenhouse gas is the elixir of life. The microbes oxidize the carbon dioxide and extract energy from the process. This means that they can exist under extreme conditions without oxygen, e.g. in hot wells. It has long been surmised that some microbes feed on rust as well as methane. Now, for the first time, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology have found the evidence to confirm this. Together with researchers from the University of Radboud they encountered a hitherto unknown microbe that converts methane to carbon dioxide with the aid of iron.

As reported in the journal PNAS by the team led by MPI microbiologist Boran Kartal, the conversion process releases reduced iron that is then available for use by other organisms. This sets a whole avalanche of processes going, and the rust-eating microbe exercises an influence on both the iron and the methane cycles.

Primaeval microbe discovered in the laboratory

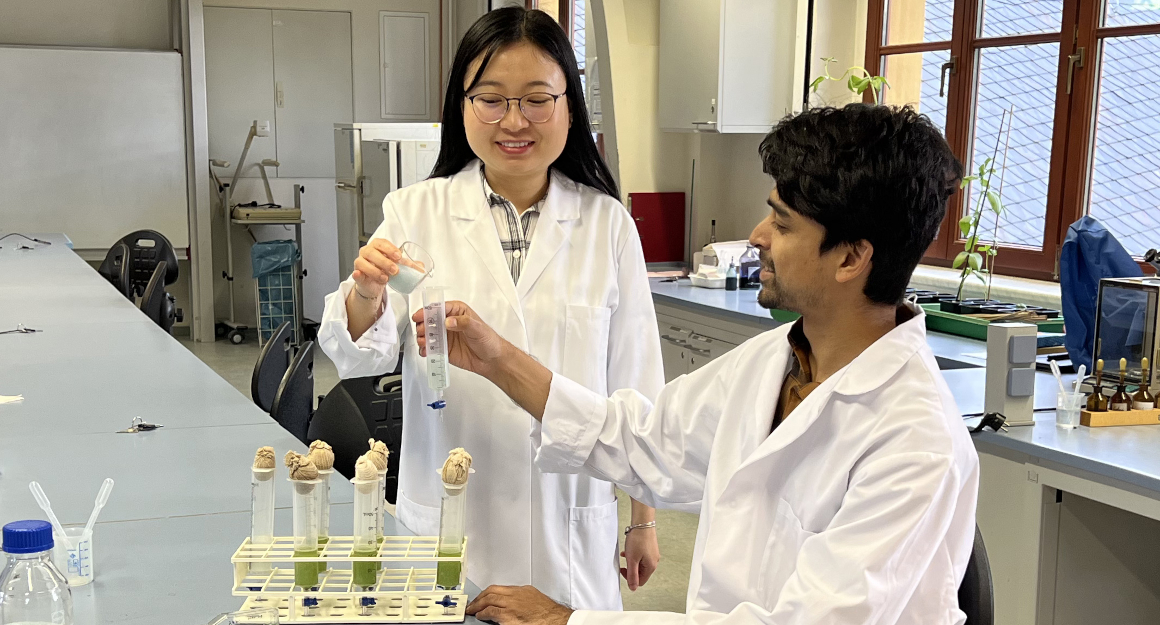

The iron-dependent methane oxidizer is a so-called archaeum (literally: 'ancient thing'). The researchers actually found the organism in an environmental sample that had been kept in the laboratory for years. The material came from the Twentekanaal in the Netherlands. "We took a look at this microorganism's genetic fingerprint and guessed that it could metabolize particulate iron – which is basically what we call rust – in the course of oxidizing methane. And lo and behold – it can," reports Boran Kartal.

The skill-set needed to clean waste water

The researchers are sure that the newly discovered archaeum plays an important role regarding emissions of the greenhouse gas methane. But that is not all. "That is important for wastewater treatment," says Kartal, who just recently transferred from Radboud University to the Max Planck Institute in Bremen. "It is possible to build a bioreactor containing two different microorganisms which can metabolize both methane and ammonium without oxygen. One could use the reactor to extract ammonium, methane and oxidized nitrogen from the wastewater simultaneously, with harmless nitrogen and carbon dioxide gas being produced as a result," explains Kartal. This study closes a significant gap in our understanding of anaerobic methane oxidation. In the next step, Kartal and his team want to establish which protein complexes are involved in this process.